If you work in cybersecurity, you probably know what a security information event management (SIEM) is. SIEMs have become one of the essential tools in managing your iInformation technology (IT) infrastructure, allowing you to capture all of the events across your entire organization into a single place for analysis and correlation. The term has been around since at least 2005 and has become a standard in the cybersecurity landscape.

The idea of a SIEM is relatively simple: collect the logs of all of the activity that is happening in your environment into a single place that allows you to easily see activity over time that may span across multiple devices and possibly even sites. Each device is configured to forward its logs to this central aggregation point, making its exploration a far simpler task than individually connecting to each device in an IT environment to look at corresponding events.

Busting at the SIEM

Like with any information centralization tool, there’s always a desire for more data. For example, your organization may stand up a SIEM and send firewall logs to it to capture data about traffic entering or leaving your environment. This is a major accomplishment! Now you’re capturing logs that may be required for compliance purposes and you’ve centralized your firewall logs into a single place to search!

But as soon as something happens on your network that looks suspicious, you’ll go to the SIEM and find the ingress or egress associated with the activity—and perhaps where the endpoint connections were made—but you’ll be missing key context about what else happened because you’re only seeing one part of the picture.

“This is an easy fix,” you’ll tell yourself, and you’ll wire up more data sources into the SIEM, such as your internal databases, or web applications, or Active Directory servers. Now when something strange happens on the network, you can see the ingress point and possibly a landing zone where the attack may be targeting such as your domain controllers.

Unfortunately, our networks are no longer walled gardens. We have centralized identity providers like Microsoft Entra ID or Okta that literally grant the keys to the kingdom to your users, including applications scattered across one or more cloud providers like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

Since we’ve decentralized our IT infrastructure, our collective attack surface has expanded and an attack path may route through devices scattered around the world.

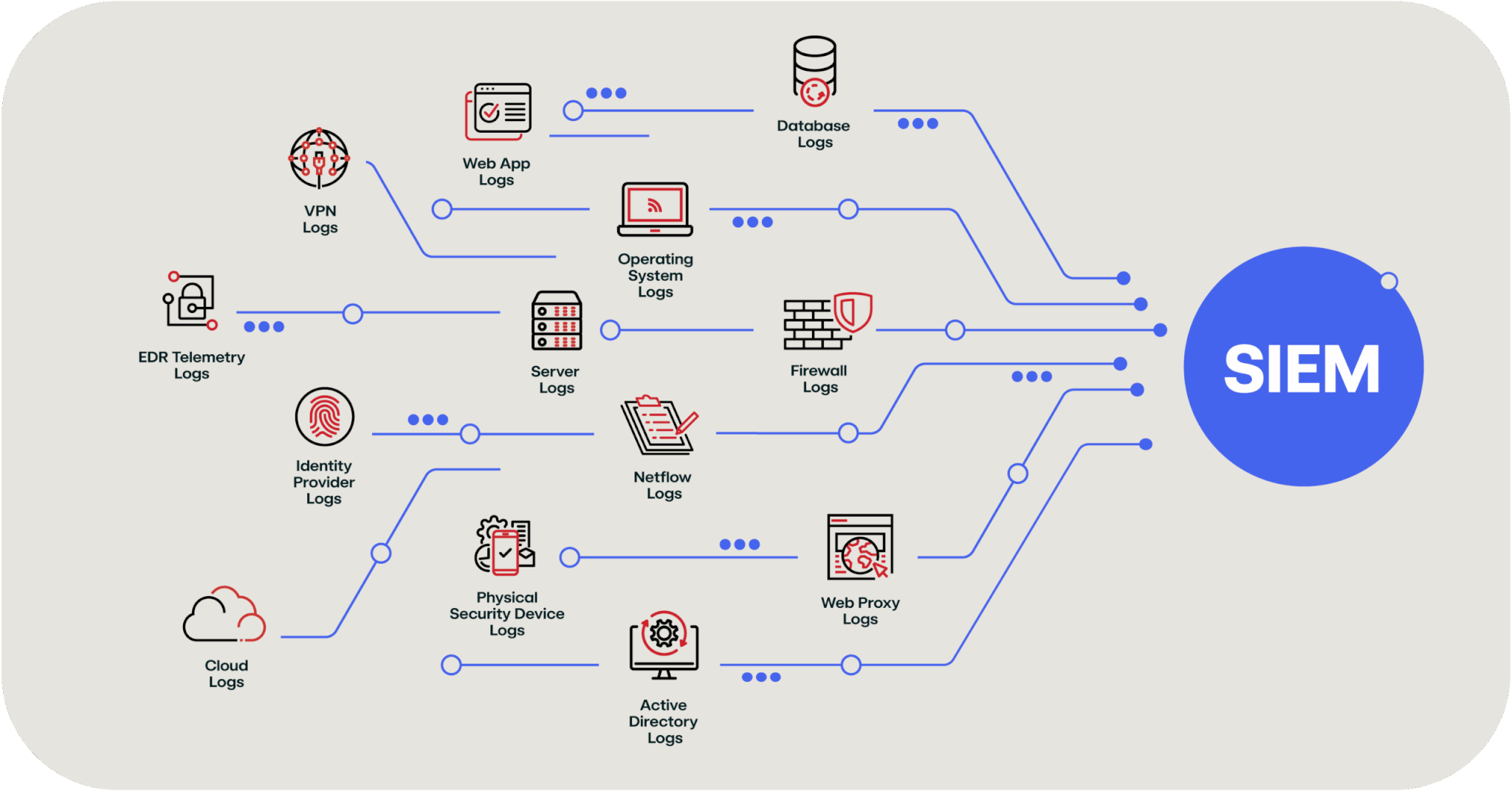

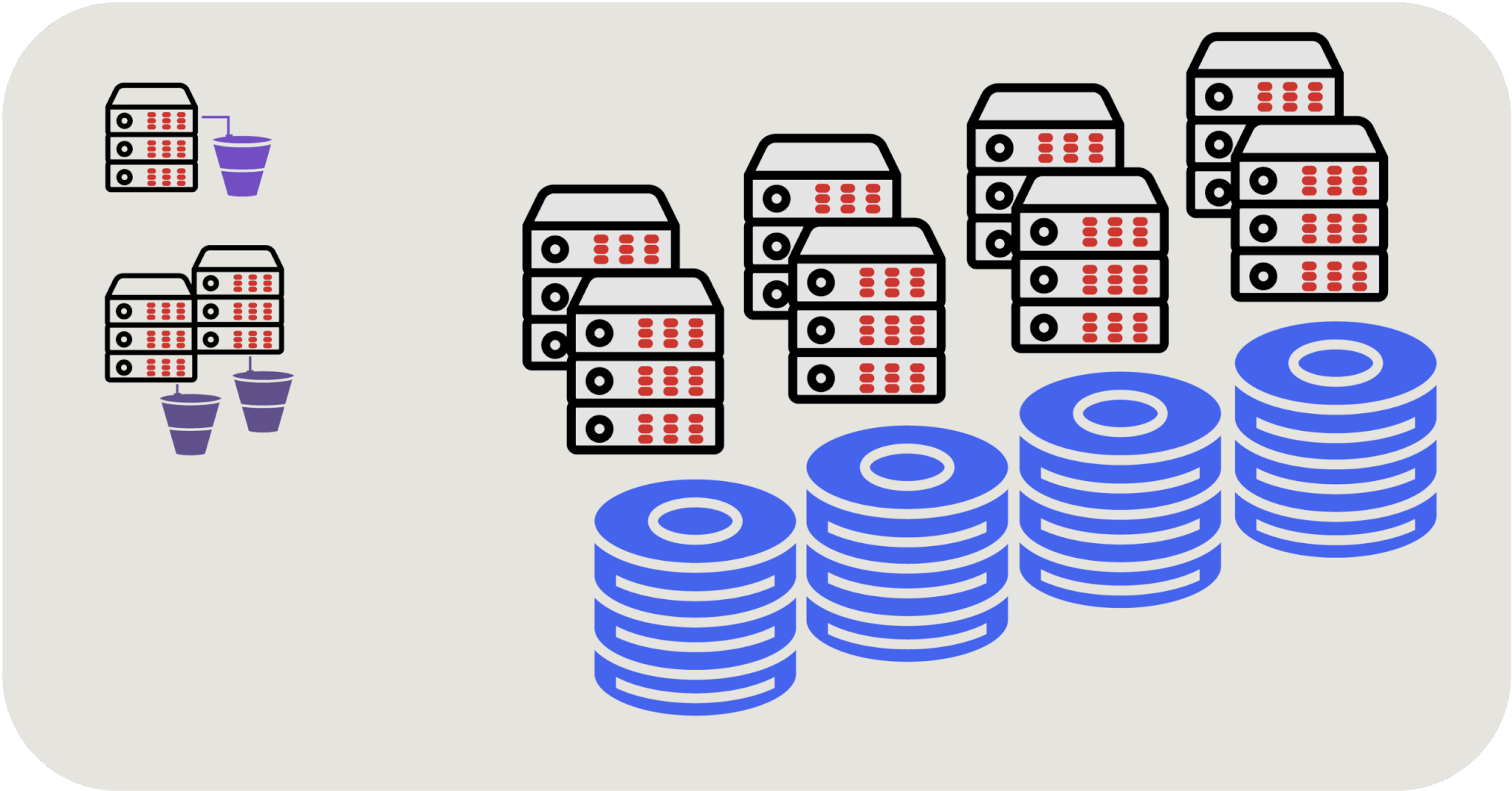

These days, for a complete picture of your IT infrastructure, you’ll need to connect all of these data sources into your SIEM to monitor potential indicators of compromise (IOCs) or forensically construct the events that lead to a breach after the fact. Before you know it, your SIEM will look like the diagram below, with dozens of extremely voluminous data sources like cloud audit logs and endpoint telemetry streaming into it to give you full visibility of everything happening across your enterprise.

An example of the data streams that may feed an enterprise SIEM

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with this approach. You need visibility into your environment and, historically, the way to do this was to funnel all of the data into your SIEM. The catch, however, is that SIEMs charge you by the amount of data ingested and stored. So as your IT footprint grows (or, more specifically, as the data being sent by your IT footprint grows), so does your SIEM bill.

Security team budgets are usually stretched pretty thin to begin with but now if you’re paying a significant amount of your budget to your data aggregation tool, you’re forced to make some tough choices. This is where the new* technology of data lakes comes in, and how they can help solve the budget problems we just highlighted.

*Note: I say “new”… but it’s not really. It’s pretty old tech. I’ll get to that later.

But before we dive into data lakes, let’s talk through the architecture of a SIEM a bit more to explain where that major cost driver is coming from, as it’s important to understand how a data lake actually helps.

SIEM cost challenges

Why is it so expensive to push this much data into a SIEM? To understand the answer to this question, let’s take a close look at an open source product called OpenSearch.

OpenSearch is a fork of Elasticsearch and Kibana and, while it does not match the internal architecture of large SIEM providers, the basic technology is similar and it allows us an easy way to understand how it works and where the cost drivers are.

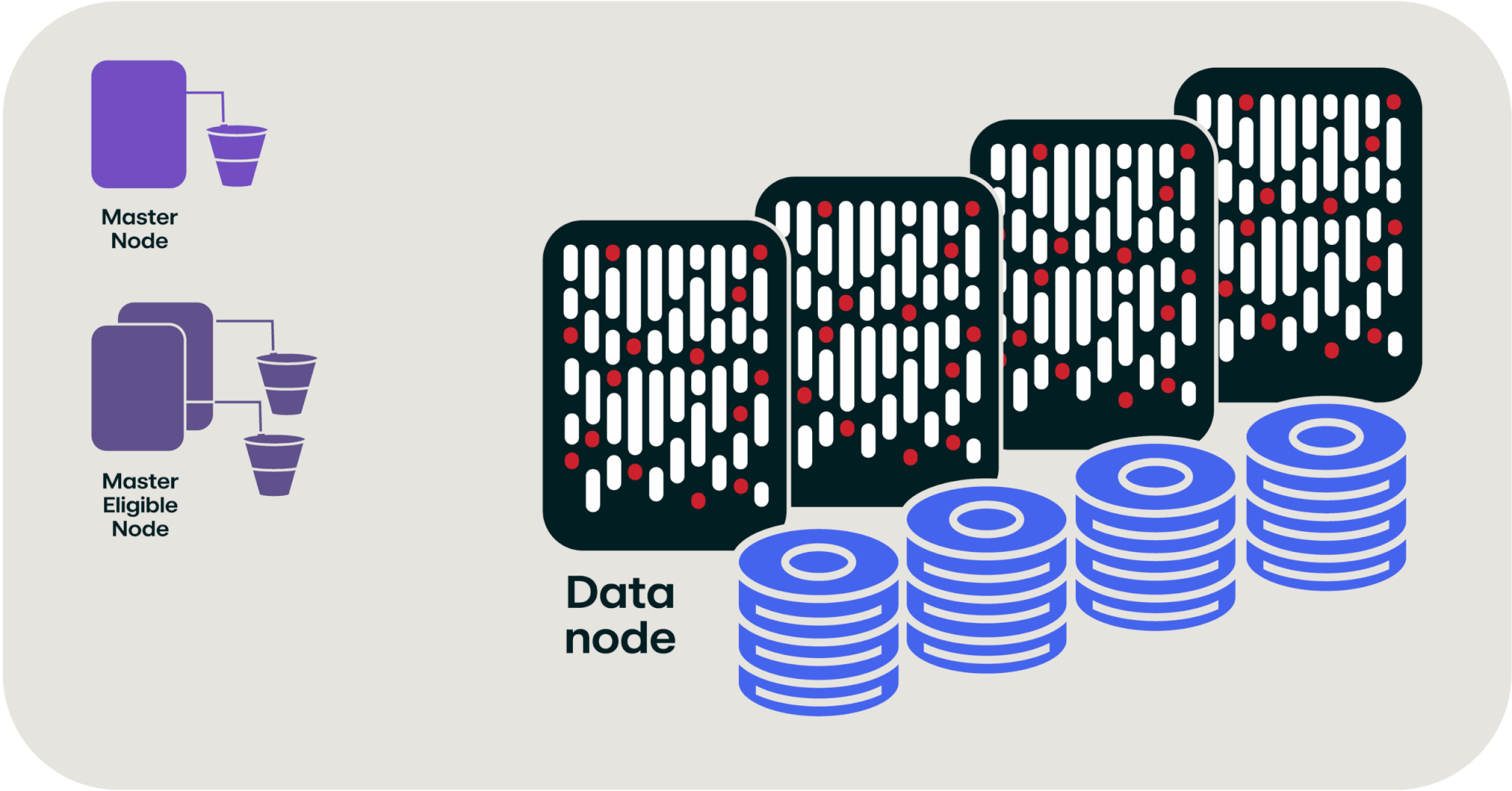

For this example, it’s easier to talk specifics instead of abstract concepts—let’s say we’ve got an OpenSearch cluster that holds 105 terabytes of data. For starters, OpenSearch isn’t just one computer; it’s several of them networked together to provide fast access to data stored across all of them. In this architecture, you have a master node and several master-eligible nodes to provide a high-availability control plane to your database; these don’t hold data, but they’re managing all the other computers that are part of this OpenSearch cluster. Then you’ve got some large computers to manage all of the data; for a 105 terabyte cluster, you’d have 12 nodes with 32 cores and 256 gigabytes of memory as well as nine terabytes of disk storage per node.

Rendering of an OpenSearch cluster (not to scale)

So, to hold all of this data and make it easily accessible, we’re looking at 15 or more separate computers. If you’ve spent any time working in IT, you know that a fundamental truism of IT is…renting computers is expensive.

We’re starting to get a hint as to why storing this much data in a SIEM costs so much; it takes a lot of big computers with big disks attached to handle the storage and indexing of all of this data.

Show me the money

Let’s take a closer look at the costs associated with these computers because they can start to reveal some interesting details.

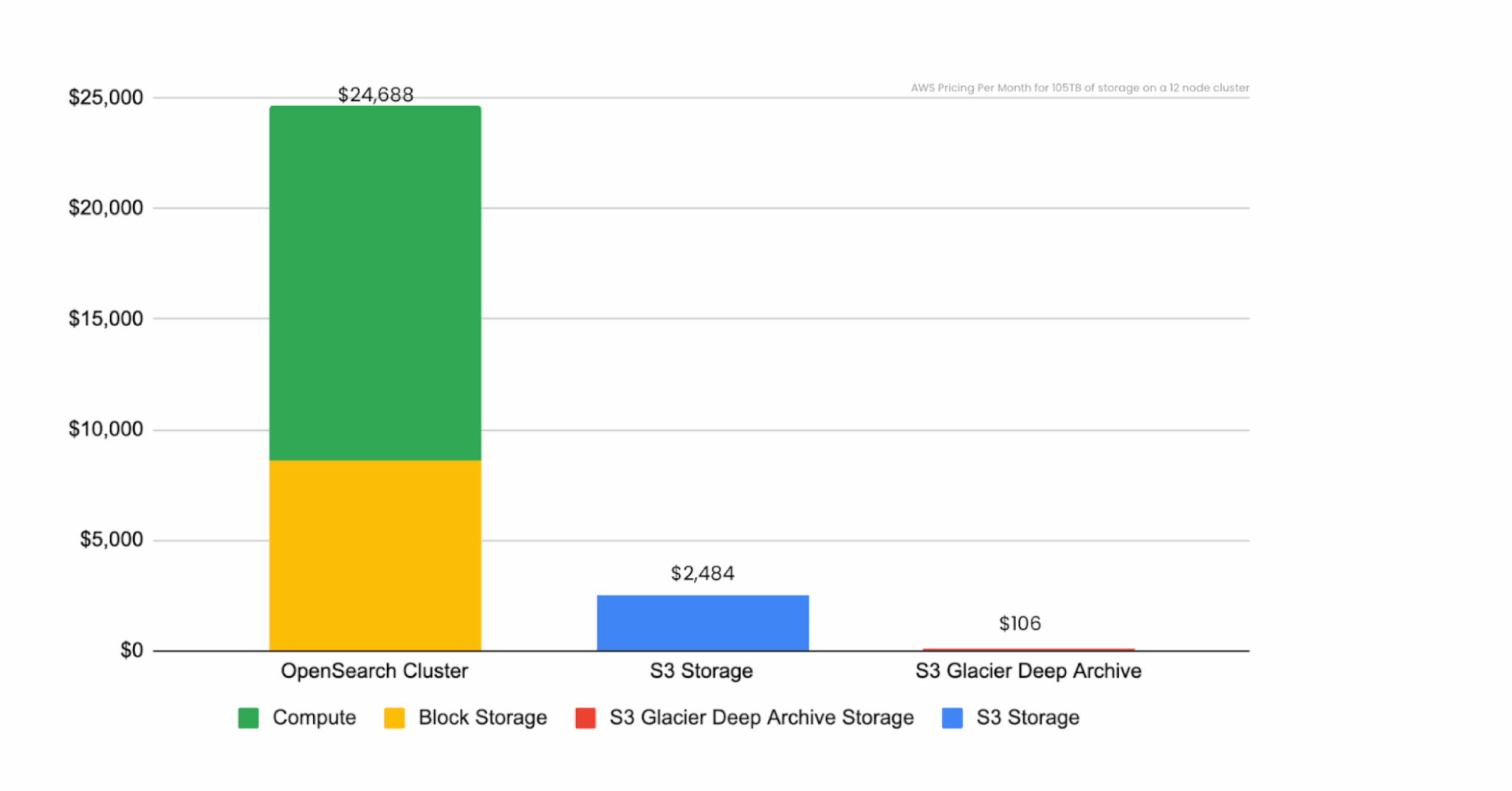

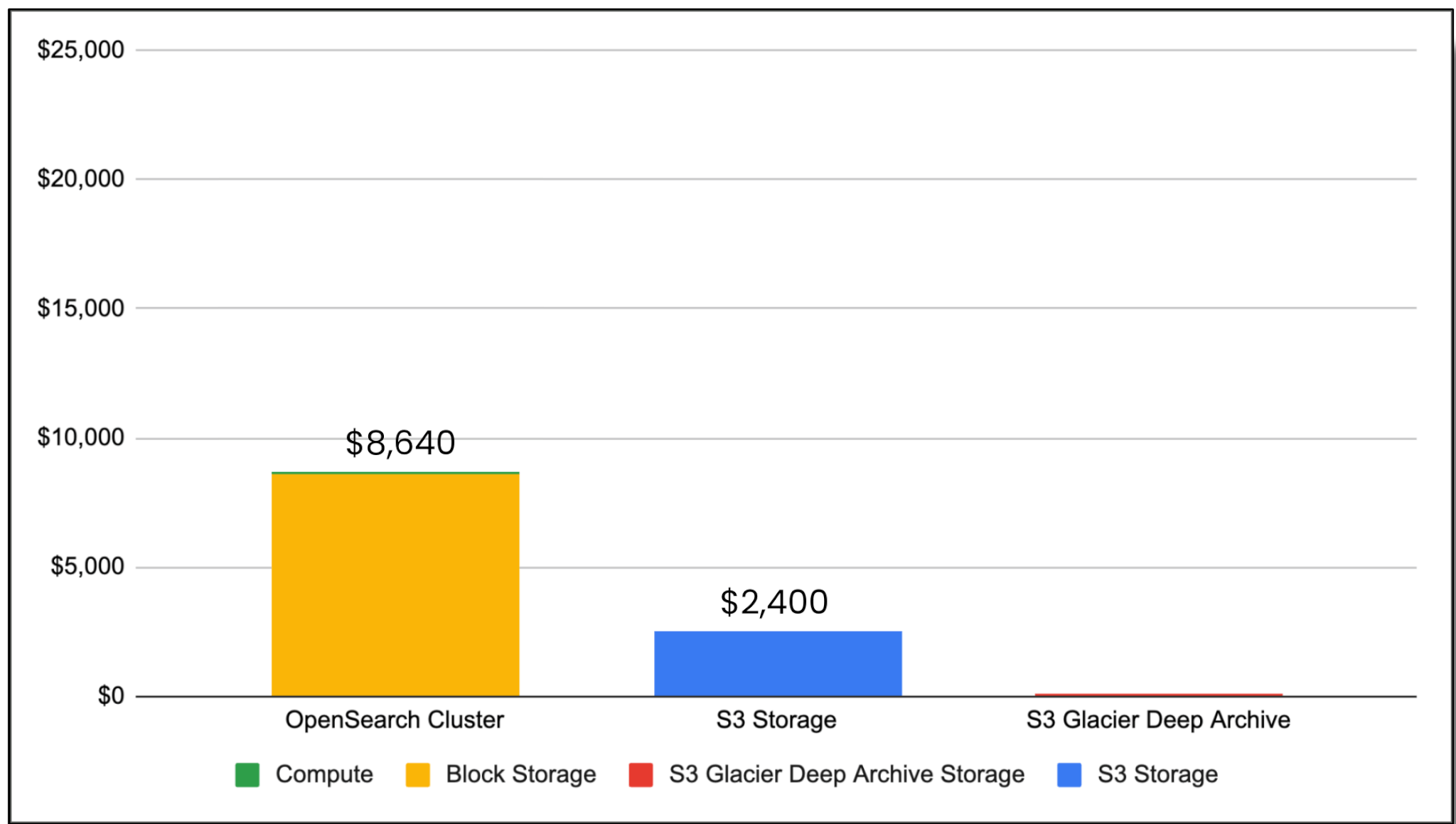

If we were to build this OpenSearch cluster, it would cost us $24,688 per month (using AWS us-east-2 region as our cost basis). But the interesting thing is that the data storage is only 35 percent of that cost ($8,640 per month). This cost differential is really the crux of where a data lake comes into play… but I’m getting ahead of myself.

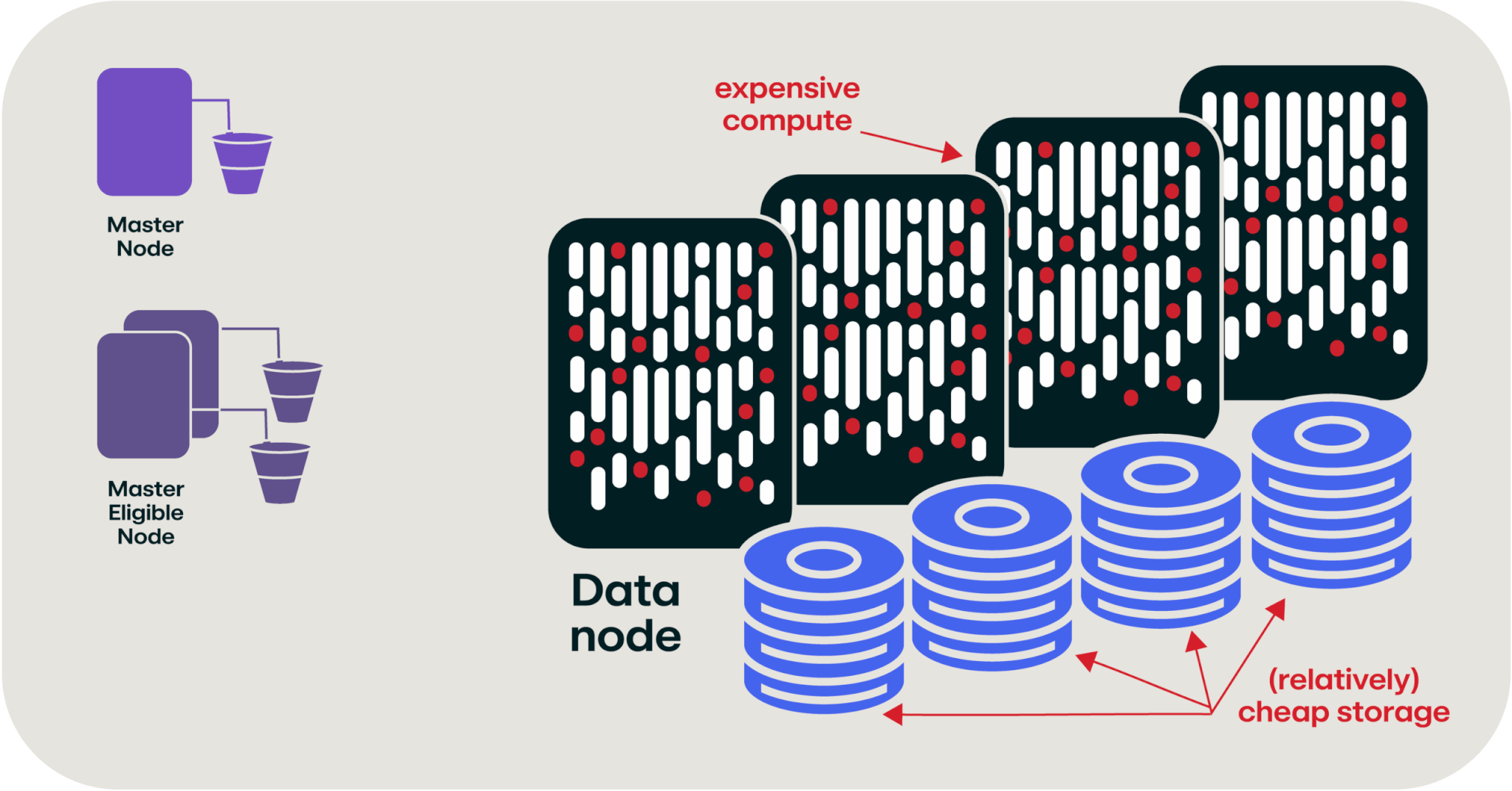

If we take another look at our OpenSearch cluster, you’ll see that the “compute” part of the cluster is the majority of the cost of the cluster, and the storage is (relatively) cheap in comparison.

OpenSearch cluster with expensive compute costs and relatively cheap storage

But why? The answer is that in our giant cluster of servers, we have 423 cores and three terabytes of RAM, which is really expensive to rent (or buy) in the cloud. What if, hypothetically, you could strip the computers away from the data and just have the storage? This graph shows you the relative cost of 105 terabytes of storage when attached to these computers vs. common cloud object storage (like Amazon S3), and cloud cold storage (S3 Glacier Deep Archive).

Storage cost comparison without data lake

So let’s take a pause here for a second and finally talk about data lakes.

What’s a data lake, anyway?

So, we’re well into this article by now and I haven’t actually described what a data lake is yet. Let’s review what the hyperscalers call it:

AWS’s definition: A data lake is a centralized repository that allows you to store all your structured and unstructured data at any scale.

Microsoft’s definition: A data lake is a centralized repository that ingests, stores, and allows for processing of large volumes of data in its original form.

Google’s definition: A data lake is a repository that stores, processes, and secures large amounts of data. Data lakes help businesses cut costs, manage data, and use AI.

Personally, I don’t find these definitions to provide a tremendous amount of clarity. They’re not wrong, but they’re not telling the full story either. The reality of it is that data lake technology isn’t actually new. It’s akin to gluing together a bunch of mature technologies and pretending they’re a database. All of the tech evolved from Apache Hadoop (which has been around since 2004) and Apache Spark (which has been around from 2009).

Or, if you prefer, it’s like three raccoons in a trenchcoat, calling themselves a data lake.

Let me explain further (because as cute as the raccoons are, that doesn’t really help paint a picture of what a data lake is any better than the definitions above).

Right now, our OpenSearch cluster (which is the stand-in for a SIEM) is costing about $25,000 per month; and 65 percent of that cost is compute. If we magically do away with the compute part of our SIEM, we can drop our monthly costs down to $8,640, which is the cost of the block storage attached to the computers. But, since we’re being magical here, once we disconnect those disks from a computer, we don’t need them to be “block storage” anymore.

(A quick aside: Block storage is what we all think of as the disks in our computers—they’re divided into a fixed number of blocks that are randomly accessible and files are written across these blocks.)

We can continue waving our magic wand around and change that 105 terabytes of storage into object storage.

(Another aside: When most people think of cloud file storage—like Google Drive, Dropbox, or Amazon S3—they’re often thinking of object storage. This system lets you interact with whole files, reading and writing them as single units, without providing random access to their underlying blocks.)

As shown in the graph below, switching from block storage to object storage dropped our storage costs down to $2,400! We’re now an order of magnitude cheaper than when we started in terms of cost (albeit with a lot of magic wand waving so far… but we’ll get to that later).

Storage cost comparison with data lake

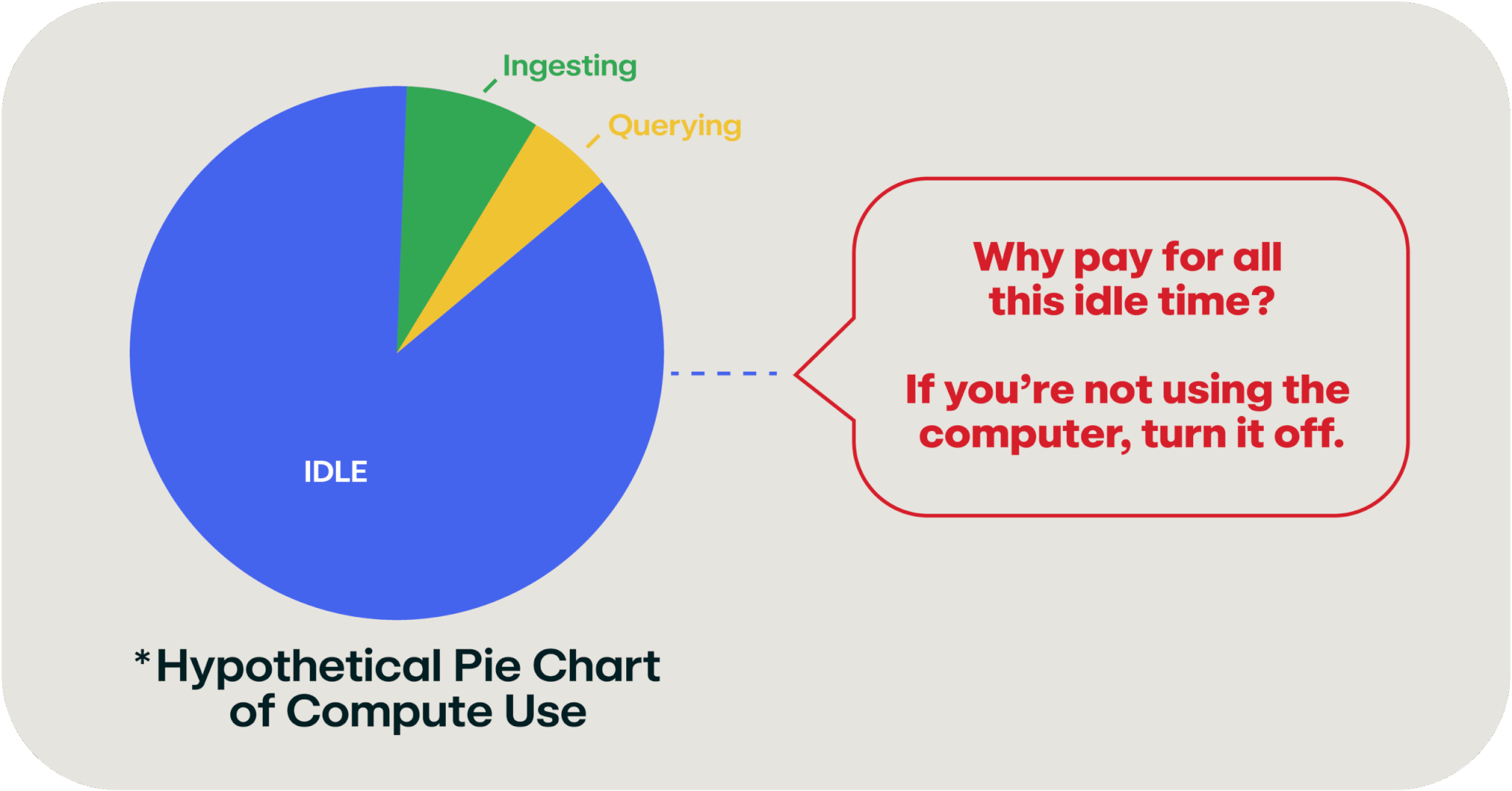

So let’s talk about those computers that I keep magically wishing away. If you think about a SIEM, how busy are those computers normally? They’re always ingesting data, as that data will always flow into the system; and your security team is probably occasionally querying the data. The rest of the time, those computers are sitting idle. And bored (computers get bored). This pie chart shows a hypothetical amount of boredom your SIEM is experiencing right this second.

Pie chart of hypothetical SIEM computer usage

It turns out that the cloud has a solution for this type of idle computer problem: serverless computing!

The ideal use case for serverless computing is to spin up the compute capacity when you need it then shut it off when it’s not in use (so you’re not paying for it). Once you’ve decoupled your data storage from the computers, this becomes a simple thing to do and it means that you can pay for a fraction of the compute horsepower that we did when we started this example.

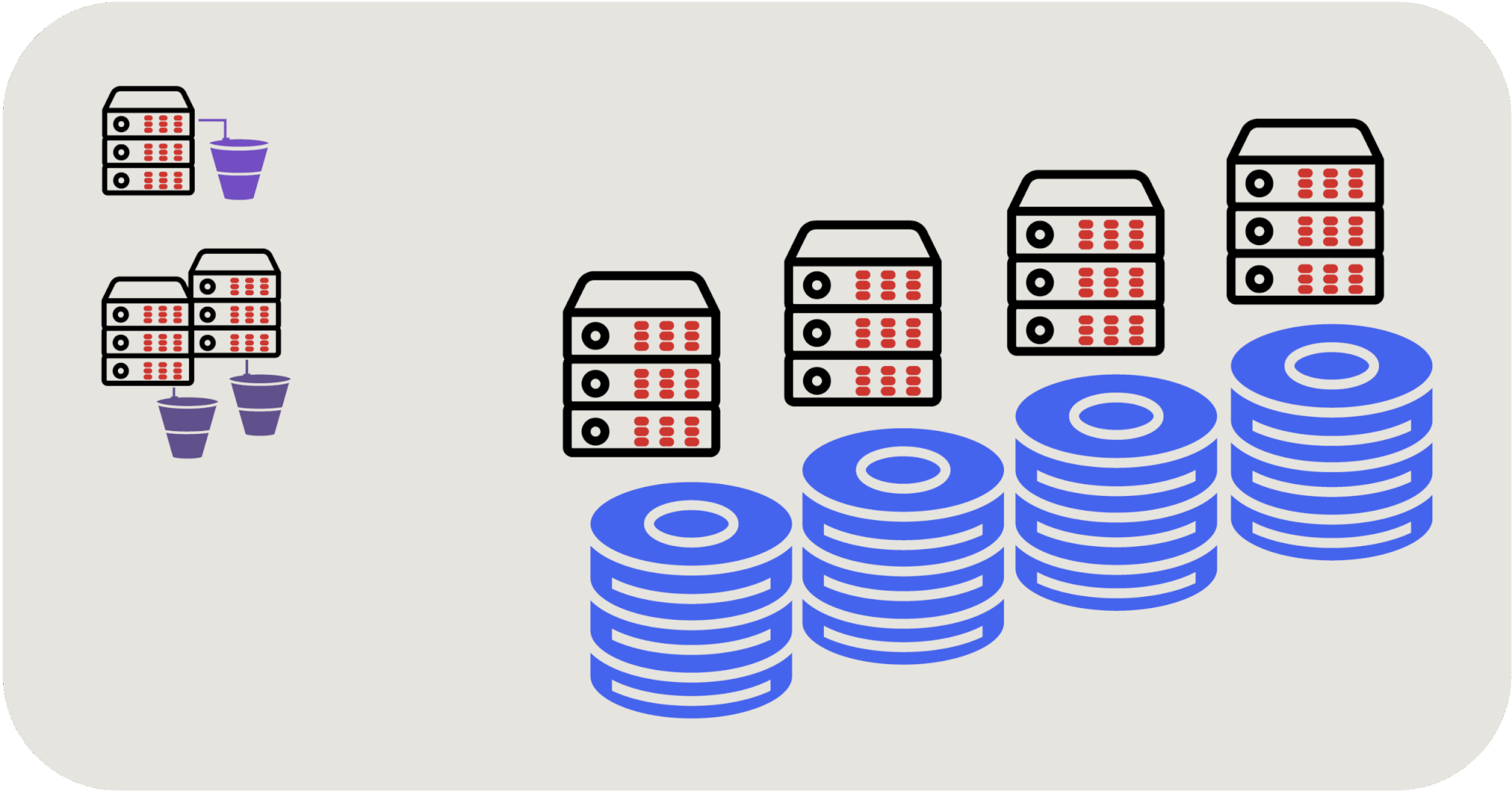

So, now our OpenSearch cluster looks something like this:

OpenSearch cluster with serverless computing

We now have a serverless compute service that can spin up and spin down on demand to access our data storage whenever we need to query it. In this scenario, the real power is that not only can we use and pay for the compute capacity that we need, we can actually increase it dynamically when we need extra compute horsepower.

OpenSearch cluster with serverless computing enabling more storage

Now that you have an understanding of the cost challenges associated with modern day SIEMs and what a data lake is, you may want to build your own. Find out how in part 2 of our Go jump in a lake series: Data storage for the win.