Adversaries are constantly seeking new and unconventional methods to achieve their objectives. Earlier in 2025, Red Canary Intelligence uncovered an interesting tactic; following a noisy spam bombing campaign, an adversary introduced their own virtual machine (VM) into a compromised environment and established persistence.

While the email bombing activity initially drew comparison to behavior we’ve seen leading to Black Basta ransomware infections, it later became clear that the threat actor had a specific set of tooling, specifically the deployment of a custom QEMU VM, which diverged from typical Black Basta tactics.

This is the first time Red Canary Intelligence has detected an adversary bringing their own QEMU VM into an environment under the guise of a technical support call following a spam bombing attack.

Here we’ll unravel the incident, exploring the initial social engineering attack, the adversary’s choice of tools, and how we pieced together the intrusion. We’ll end by discussing how the strategy represents an evolution in adversary methodology and what it means for defenders.

A familiar smokescreen: Spam bombing and social engineering

The incident began with an organization experiencing a spam or email bombing attack. This technique, wherein a victim’s inbox is flooded with thousands of unsolicited emails, has become a popular distraction tactic, and favored by ransomware groups. The goal is to overwhelm the victim, making it difficult to spot legitimate communications and prime them for a follow-up social engineering attempt.

In this scenario, the adversary wasted no time. After flooding the inbox, they initiated a call to the organization posing as a technical support representative. Their offer was simple: help alleviate the deluge. It’s a calculated maneuver, leveraging distress to gain trust.

After gaining the user’s confidence, the adversary leveraged remote assistance software Quick Assist. This legitimate, built-in Windows application allows a trusted person to take control of another computer remotely. While it can be used for support—like many remote monitoring and management (RMM) tools these days—it can be misused by threat actors to establish initial access and deploy malicious payloads.

A twist: The adversary’s virtual machine

Instead of directly dropping ransomware or a standard backdoor, the adversary used the Quick Assist foothold to introduce their own VM. Anytime an adversary leaves remnants of their activity, especially an entire file system, it presents an opportunity for forensic analysis—so that’s just what we did.

Unpacking the QEMU disk: A forensic deep dive

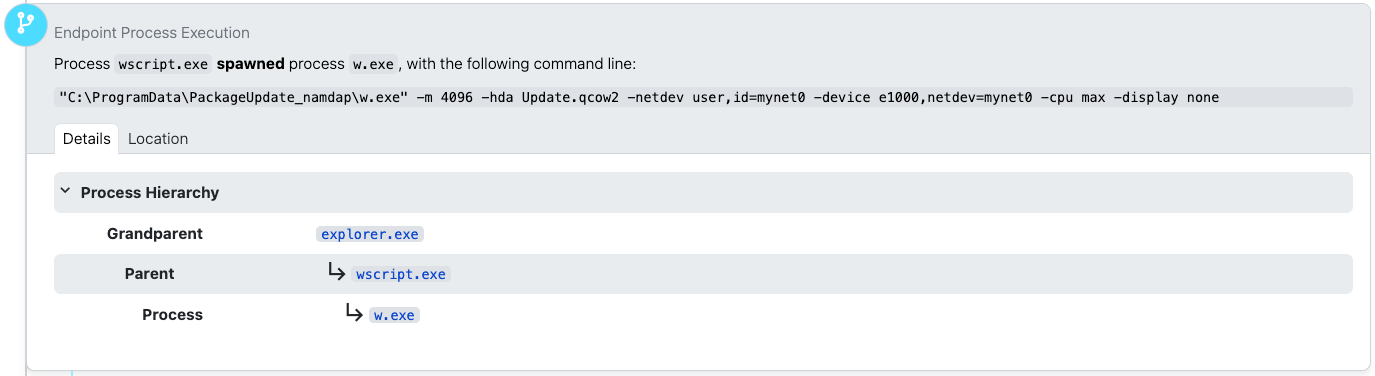

The adversary’s actions began with the execution of a Visual Basic Script (VBScript), Update.vbs. Due to Quick Assist’s nature of piggybacking on the user’s Explorer session, many of these initial actions appeared to originate from explorer.exe itself, something that might raise red flags if not for the context of the remote session.

The primary function of Update.vbs was to launch w.exe; this executable was invoked with several specific parameters:

-m 4096to allocate 4096 MB of memory for the VM- –

hda Update.qcow2to specify the virtual hard disk image - networking parameters like

-netdev user, id=mynet0 -device e1000, netde", '0', "false"

These network settings gave the VM full access to the internet, allowing for command and control (C2) communications, and crucially, permitted it to scan the local network of the compromised organization.

A quick look at the metadata for w.exe on VirusTotal immediately revealed its true identity: qemu-system-x86_64.exe, a component of QEMU, an open source emulator and virtualizer. While legitimate, its presence on a standard user’s system—especially one invoked under suspicious circumstances—is highly unusual. Most everyday users, even power users, don’t have a need for a full system emulator.

Initial network reconnaissance from within the VM

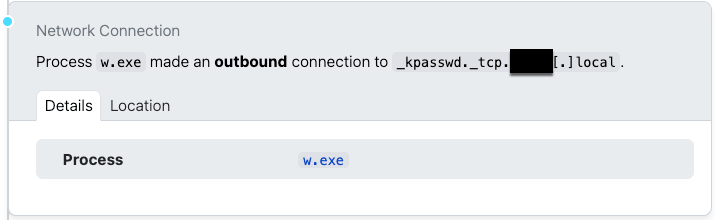

Once the QEMU VM was up and running, it started exhibiting tell-tale signs of reconnaissance. We observed numerous network connections to various local hosts; this internal scanning is a critical step for adversaries, allowing them to map out the network topography, identify potential targets, and prepare for lateral movement.

Simultaneously, the VM established external network connections. One notable connection was to marnyonline[.]com, an external domain that would later prove to be a C2 server. Another connection was made to the legitimate remote support and access software ScreenConnect. Like Quick Assist, the use of remote admin tools for malicious purposes can help adversaries blend in with normal network traffic.

Further network activity included DNS resolution requests for service records (SRV records) for the local DNS domain. These records are fundamental to how services within an organization’s network locate each other. For instance, Windows systems use SRV records to find Active Directory domain controllers. Adversaries can query these records to gain significant insights into an organization’s domain infrastructure, identifying critical servers and services for potential exploitation. This type of service reconnaissance is a primary method of understanding the target environment.

Sliver C2 and “multi-player” mode

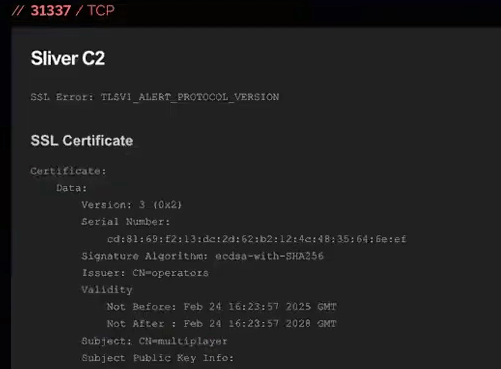

Upon investigation, Red Canary Intelligence identified an IP address (45[.]61[.]169[.]127) and discovered, via Shodan, that it was associated with Sliver, an open source command and control (C2) framework.

What made this association particularly straightforward was its configuration in Sliver. When running in “team server” mode—a configuration allowing multiple adversaries to control multiple compromised hosts from a single server—Sliver defaults to setting up a server with an SSL certificate with the subject name CN=multiplayer and issuer O=operators. While likely intended for internal team identification, this can also provide a unique fingerprint for tracking Sliver team servers via Shodan.

Reconstructing the adversary’s actions: Insights from prefetch and browser history

Performing forensic analysis, particularly with a tool like Plaso—a Python-based engine for creating digital timelines—can be a lengthy and arduous process. Analyzing an 8 gigabyte disk image, like the one left by this adversary, can generate a 200 MB spreadsheet timeline, overwhelming even robust tools like Google Sheets. Despite these challenges, such timelines are indispensable for understanding a sequence of events like those in an incident like this.

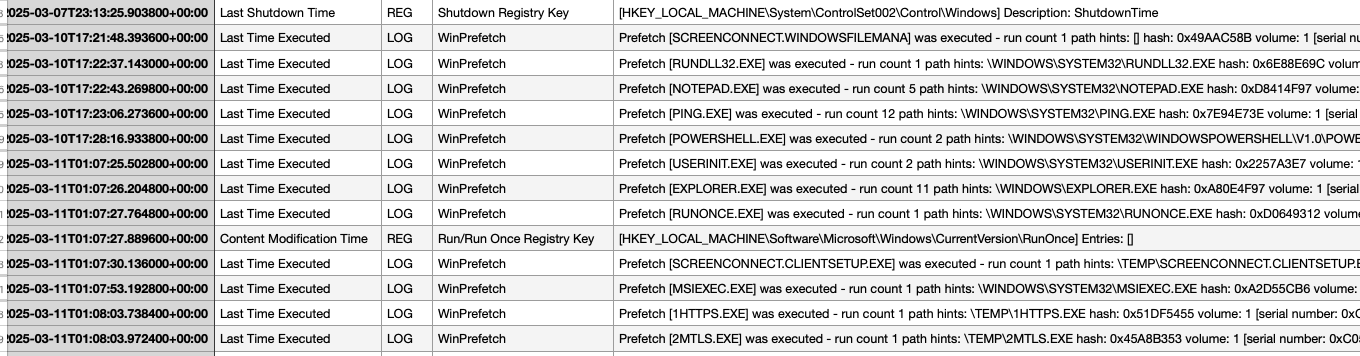

Our analysis of prefetch and application compatibility cache data provided additional insight. Prefetch files, automatically generated by Windows for performance optimization and stored in C:\Windows\Prefetch, record information about application usage. While application prefetching is disabled on Windows Server by default, the adversary’s VM was running Windows 7 Service Pack 1, where prefetch was active. This allowed us to determine which programs the adversary ran, even without command-line arguments. While they likely didn’t anticipate someone capturing their disk, disabling prefetch would have been a basic anti-forensic measure.

We determined the VM’s operating system by examining the file properties of the NT OS kernel executable, ntoskrnl.exe, which reported a file version of 6.1.7601—identifying the OS as Windows 7 Service Pack 1. It’s plausible the adversary used a pre-built VM template, perhaps one of the older, freely distributed, pre-built Microsoft VMs for testing purposes, and then customized it.

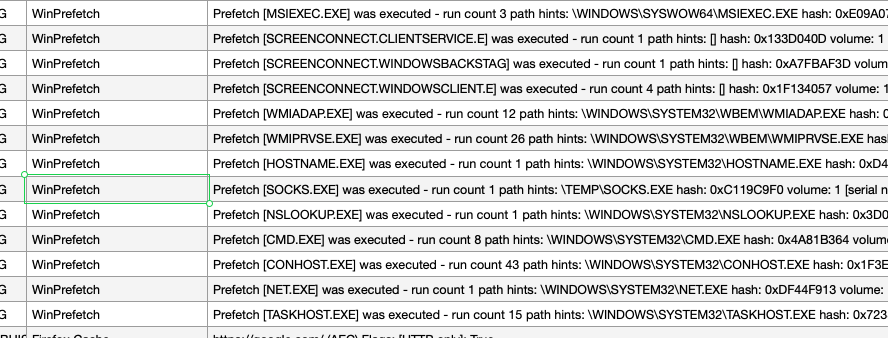

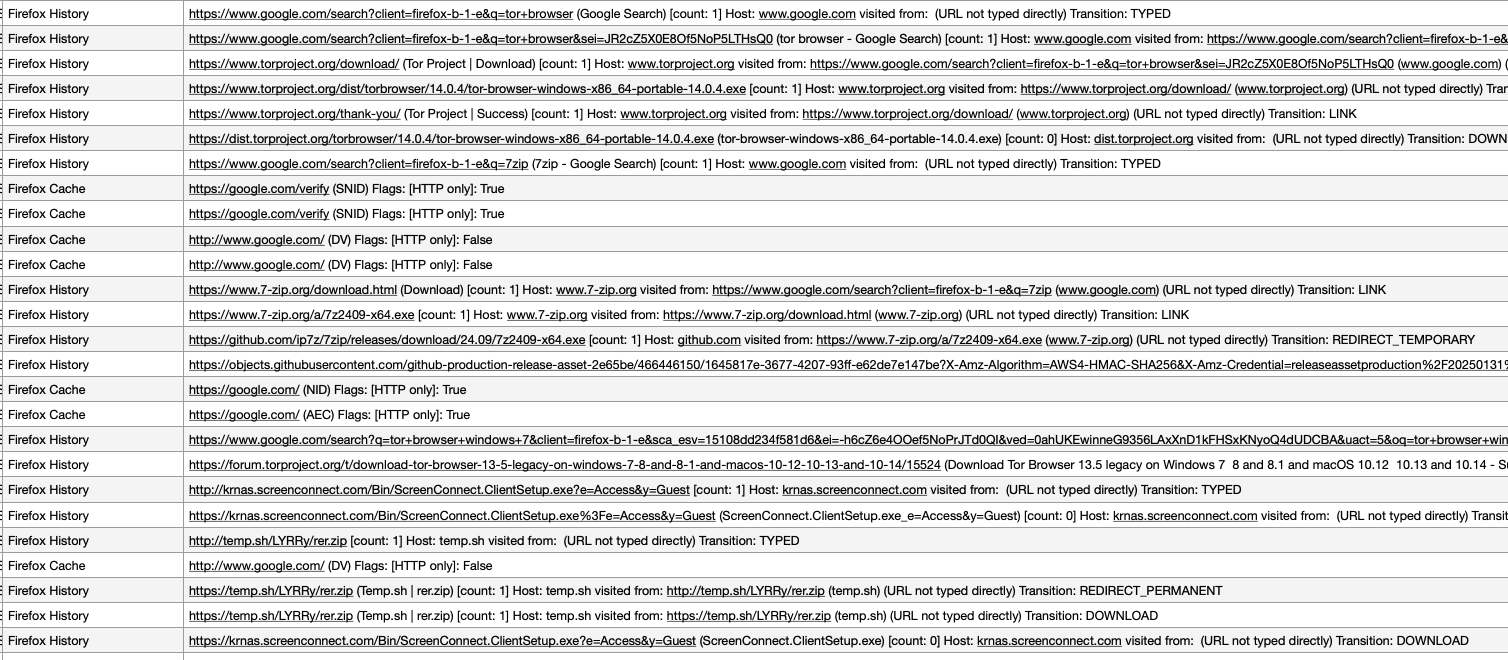

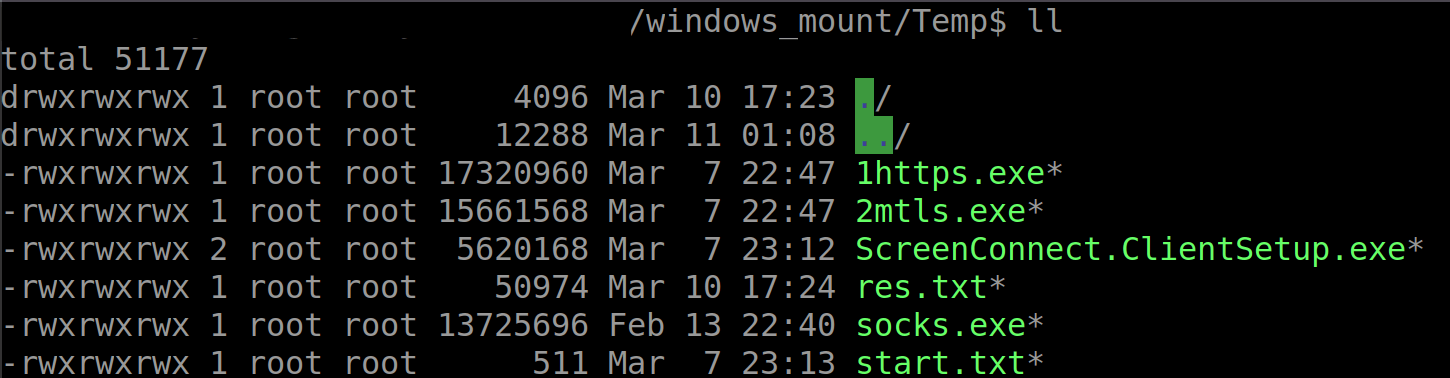

The prefetch data also revealed a timeline of activity within the VM. The first recorded action was the use of ScreenConnect, followed by a series of program executions: ping.exe, Notepad, and powershell.exe. We also identified two particularly interesting executables in the TEMP folder: 1HTTPS.EXE and 2MTLS.EXE, along with SOCKS.EXE. Further prefetch entries showed execution of NSLOOKUP.EXE (possibly corroborating the earlier service record lookups) and NET.EXE (potentially for mapping remote shares).

Beyond executables, Plaso can also parse browser databases to reconstruct internet history. Unsurprisingly, the adversary’s first action after what appeared to be a fresh Windows installation was to install a non-Internet Explorer browser: Firefox. The initial Firefox activity included searches for the Tor browser, a download of 7-Zip, a ScreenConnect installer, and an archive named rer.zip. The rer.zip file was no longer present on the disk, suggesting it was deleted after use. The adversary’s use of Tor aligns with efforts to anonymize their activities, while 7-Zip is a common utility for archiving and exfiltrating data.

The adversary’s toolkit: Sliver, ScreenConnect, and Qdoor

A deeper dive into the TEMP folder within the virtual disk yielded a treasure trove of information. Alongside the previously identified 1HTTPS.EXE and 2MTLS.EXE, we found ScreenConnect.ClientSetup.exe, res.txt, and start.txt.

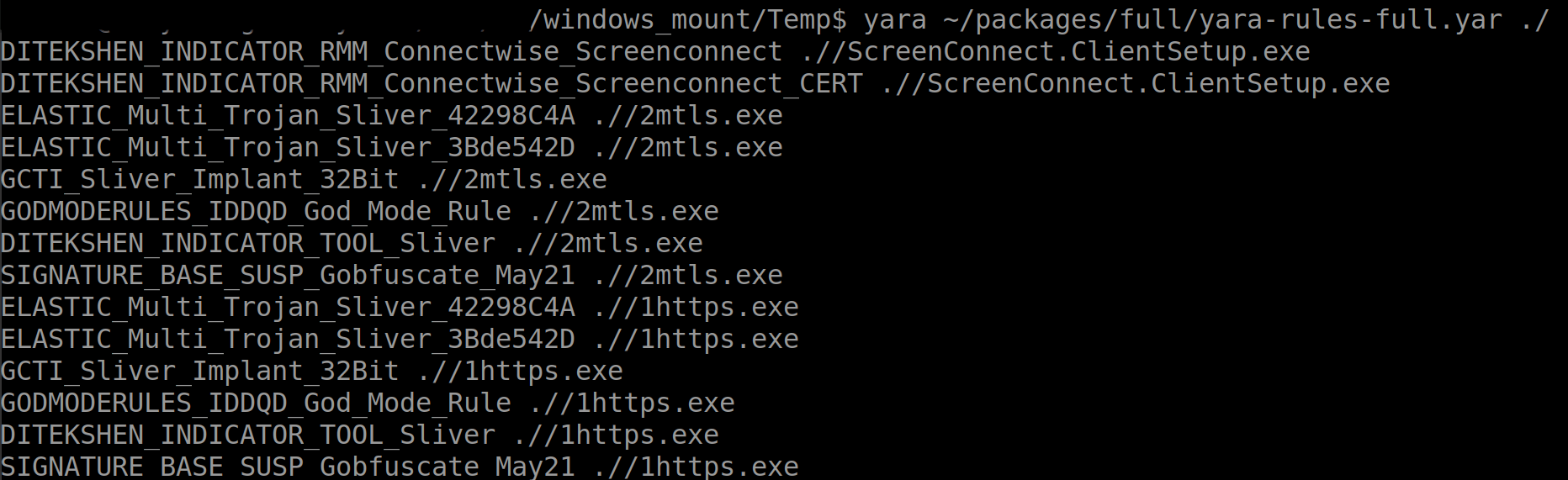

A YARA scan confirmed ScreenConnect.ClientSetup.exe was legitimate ScreenConnect software, while 1HTTPS.EXE and 2MTLS.EXE were identified as Sliver implants, likely obfuscated using gobfuscate. SOCKS.EXE, however, did not initially trigger any known YARA rules, posing a temporary mystery.

The res.txt file was particularly illuminating. It contained 50,974 bytes of text, revealing the adversary’s reconnaissance findings. The file documented a ping scan, with each entry representing a single ping instance. This “one ping per instance” approach suggests the adversary was deliberately trying to be stealthier and faster than the default Windows ping behavior, which sends four pings per target. This granular scanning allowed them to map the network discreetly.

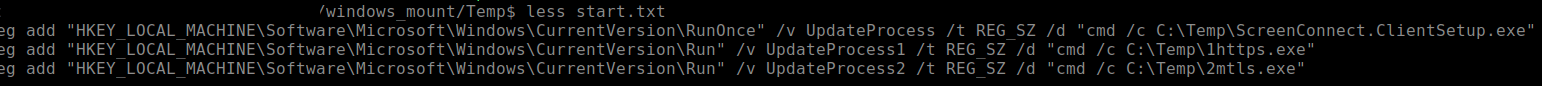

The start.txt file revealed the adversary’s persistence mechanisms. While it might seem odd for an adversary-controlled VM to need persistence, consider its context: this VM is essentially a rogue device on the victim’s network. Just like any other remote access tool, the adversary needs to ensure their access remains viable if the VM or the host machine restarts. The persistence configuration in start.txt ensured ScreenConnect and the two Sliver processes (1HTTPS.EXE and 2MTLS.EXE) would execute automatically. This redundancy—using both ScreenConnect and two Sliver variants—highlights the adversary’s desire for resilient access, anticipating potential network segmentation or firewall rules that might block one access vector but not another. It’s a scattershot approach to maintain control.

VMray analysis of 1HTTPS.EXE in a Windows 7 SP1 isolated environment confirmed it was a Sliver beacon, attempting to communicate with marnyonline[.]com. Similarly, 2MTLS.EXE was confirmed as another Sliver implant, trying to reach 45[.]61[.]169[.]127 over port 8443. Both appeared to be straightforward Sliver implants, designed for beaconing and basic command execution.

To further analyze SOCKS.EXE, we used VMray’s dynamic analysis to execute it in an isolated network environment. The initial VMray analysis showed SOCKS.EXE attempting to connect to 88[.]119[.]167[.]239, delaying execution, and dynamically resolving API functions but without clear classifications.

A link from LinkedIn

While an exhaustive search for 88[.]119[.]167[.]239 on VirusTotal and other open-source intelligence platforms yielded little, an unusual clue emerged: a LinkedIn Pulse post from ConnectWise, discussing how the BlackSuit ransomware group was leveraging a network tunneling backdoor it dubbed “QDoor.”

Although a YARA rule from the post didn’t immediately match SOCKS.EXE, the network address listed in it, 88[.]119[.]167[.]239, was a direct hit. A subsequent VirusTotal upload of SOCKS.EXE by a third party later corroborated this, with its reputation eventually updating to QDoor, suggesting it’s part of the adversary’s arsenal. Looking at the malware’s behavior in VMray, including attempts to gather information from the software framework Qt Project, including qtlogging.ini and qt.conf was also consistent with known QDoor characteristics as outlined by ConnectWise.

Deleted artifacts and missed opportunities

Part of a thorough forensic investigation involves attempting to recover deleted files. We mounted the QEMU disk image and used The Sleuth Kit with Foremost, a console program that recovers files based on header, footer, and internal data structures, on the unallocated blocks of storage. This process yielded several ZIP files and various image files, mostly remnants of program installations or deletions.

Interestingly, the adversary had placed the Tor browser and WinSCP, a popular free file manager for Windows, onto the image at some point, but these were not found installed on the active file system. This suggests a “prep” phase where these tools were included, followed by a “deployment” phase where they were removed, perhaps to reduce the disk footprint or evade detection.

The presence of volume shadow copies (VSCs) on the VM offered another avenue for data recovery. VSCs store previous versions of files and system states. While we managed to recover a Tor browser installation from a VSC, we were unable to retrieve any browsing history. Tor browser is designed to not store cache or internet history data to disk upon shutdown, which unfortunately meant no historical data was available for analysis, even through VSCs.

The novelty of the technique: A shift in tactics

The deployment of a QEMU VM by an adversary isn’t entirely unprecedented. We’ve seen affiliates of the Ragnar Locker ransomware use stripped-down VirtualBox VMs in the past to evade antivirus detection and establish a stronger foothold within compromised networks. Earlier this year, Sophos saw an adversary using similar tools within a QEMU virtual machine to compromise a domain services account before installing a commercial RMM. Kaspersky Lab has also reported on adversaries using QEMU virtual machines for network tunneling, bypassing security controls.

However, the series of events here marks an interesting deviation: This is the first time Red Canary Intelligence has detected an adversary bringing their own QEMU VM into an environment under the guise of a technical support call following a spam bombing attack. This blend of social engineering, legitimate tool abuse, stealthy persistence and novel payload delivery suggests the adversary behind this incident prioritizes complete control over their operational environment.

Implications for defense

This incident serves as a good reminder that adversaries are continuously adapting their tactics. In this incident, deploying their own virtual machine offers several advantages to an adversary:

- Isolation: The VM creates an isolated environment for their tools, making it harder for host-based security solutions to detect and analyze them directly.

- Portability: The entire adversary environment can be pre-configured and quickly deployed.

- Stealth: Using a legitimate virtualization tool like QEMU and masquerading as technical support helps blend into benign activity.

- Persistence: The VM acts as a persistent entry point, potentially circumventing direct endpoint controls.

For defenders, the incident underscores the need for a multi-layered security strategy. Beyond robust email filtering and endpoint detection and response (EDR), organizations must prioritize:

- Enhanced social engineering training: Users need to be highly skeptical of unsolicited technical support, especially if it follows unusual activity like a spam bombing.

- Strict remote access policies: Implement granular controls over remote assistance tools like Quick Assist, and monitor their usage rigorously.

- Network segmentation and monitoring: Limit lateral movement within the network and actively monitor for unusual internal scanning, DNS queries, and external C2 communications, even from seemingly internal hosts.

- Anomaly detection: Behavioral analytics that can detect the abnormal execution of virtualization software on endpoints that don’t typically use them.

- Threat intelligence sharing: Staying informed about novel adversary tactics, such as the unique fingerprint of Sliver team servers.

By understanding the full lifecycle of this attack, from the initial distraction to the forensic reconstruction of the VM’s contents, organizations can better prepare to detect and defend against these increasingly sophisticated and innovative threats.

Indicators of compromise

| Indicator | Notes |

|---|---|

| Indicator:

| Notes: Sliver C2 |

| Indicator:

| Notes: QDoor C2 |

| Indicator:

| Notes: Legitimate QEMU emulator SHA256 |

![Process w.exe making an outbound connection to marnyonline[.].com](https://redcanary.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/image8.png)