In mid-October, a variety of detection analytics alerted the Red Canary CIRT to execution, reconnaissance, and lateral movement activity on the network of a medical center. Within minutes, we observed Cobalt Strike and other malicious tools that all pointed toward a troubling conclusion: the hospital was probably a few hours away from a full-blown Ryuk ransomware outbreak. Thanks in no small part to our incident response partners at Kroll, whose Responder team rapidly engaged and began active containment steps as we detected threats, that didn’t happen.

This week, news has spread that many hospitals in the United States are being attacked by Ryuk ransomware—and are very likely experiencing some version of what we’ve just described. Despite being in the throes of a pandemic that’s already over-burdening global public health infrastructure, ransomware crews have been escalating their operations against hospitals for months now.

These attacks are abhorrent. The people responsible for them are despicable. And we, like DHS CISA, Mandiant, and others in the information security community, want to help the hospitals that care for all of us however we can. So we’re sharing the details of how we thwarted these operators earlier this month—in the hopes you can take this information and better protect your own organizations.

Background

We’ve been following all the recent reporting and tweets about hospitals being attacked by Ryuk ransomware. But Ryuk isn’t new to us… we’ve been tracking it for years. More important than just looking at Ryuk ransomware itself, though, is looking at the operators behind it and their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)—especially those used before they encrypt any data. The operators of Ryuk ransomware are known by different names in the community, including “WIZARD SPIDER,” “UNC1878,” and “Team9.” The malware they use has included TrickBot, Anchor, Bazar, Ryuk, and others.

Many in the community have shared reporting about these operators and malware families (check out the end of this blog post for links to some excellent reporting from other teams), so we wanted to focus narrowly on what we’ve observed: BazarLoader/BazarBackdoor (which we’re collectively calling Bazar) used for initial access, followed by deployment of Cobalt Strike, and hours or days later, the potential deployment of Ryuk ransomware. We have certainly seen TrickBot lead to Ryuk ransomware in the past. This month, however, we’ve observed Bazar as a common initial access method, leading to our assessment that Bazar is a greater threat at this time for the eventual deployment of Ryuk.

What we’ve seen and how you can detect it

While every ransomware outbreak can play out in different ways, we want to focus on the attack we saw in mid-October and stopped before ransomware was deployed. As we walk through this specific attack, we’ll identify 10 detection opportunities that work for us—and we hope they’ll work for you too. This attack can serve as a functional example for what you might expect to see if you’re responsible for defending a healthcare organization.

If you’re interested in the MITRE ATT&CK® techniques covered by this incident, check out the ATT&CK Navigator layer here. You can learn more about ATT&CK Navigator here.

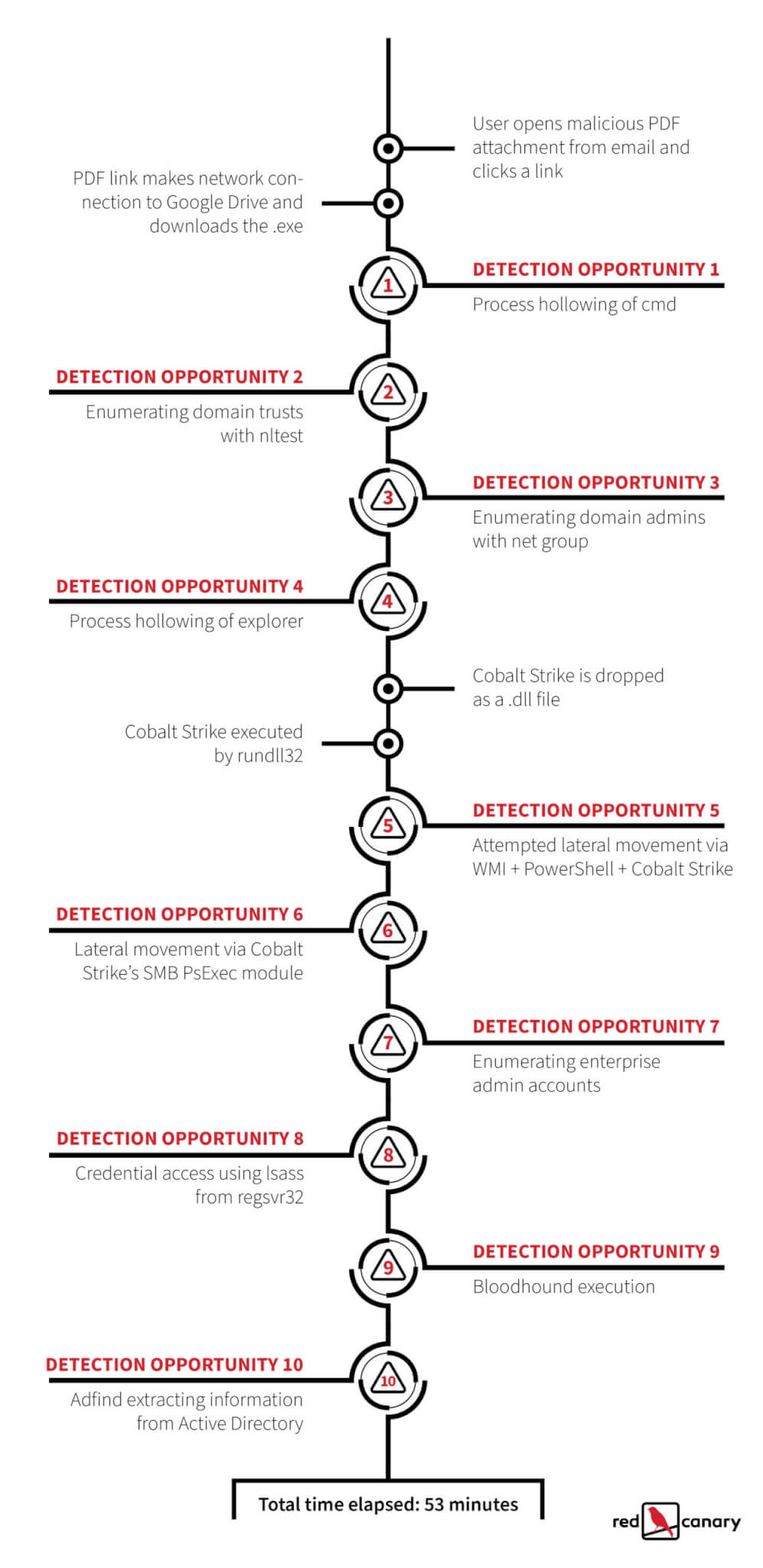

This graphic provides an overall representation of how the attack unfolded. We’ll dive into the details, complete with detection opportunities, below.

Initial access came by way of a phishing email containing a PDF attachment. The user opened this attachment and clicked on a link in the PDF, which connected to Google Drive and downloaded a file named Report[mm]-[dd].exe (for example, the file name would be Report10-29.exe if the email was delivered on October 29). This .exe is known as Bazar, which has different components known by the community as BazaLoader, BazarLoader, and BazarBackdoor.

Detection Opportunity 1: Process hollowing of cmd.exe

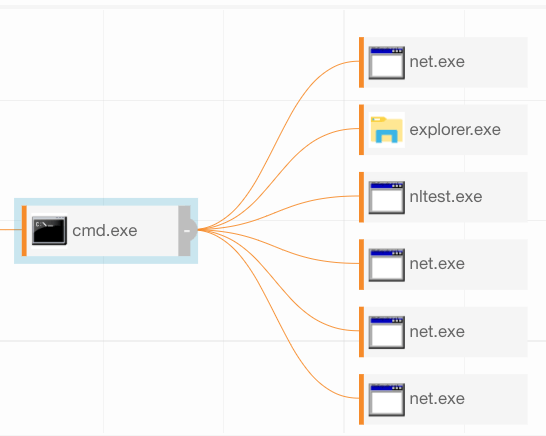

This .exe file used process hollowing techniques to inject into cmd.exe. You can identify this process hollowing, as we did, by looking for instances of the Windows Command prompt (cmd.exe) executing without any command-line parameters and establishing a network connection. If that’s too noisy, you could try limiting the network connections to port 443 or 53. You could also limit false positives by looking for child processes spawned by the hollowed cmd.exe process. Typical child processes associated with Bazar include: cmd.exe, svchost.exe, explorer.exe, nltest.exe, and net.exe, as shown in the process tree below.

Detection Opportunity 2: Enumerating domain trusts activity with nltest.exe

We then observed several reconnaissance commands associated with Bazar. Specifically, we observed the adversary using nltest.exe to make domain trust determinations. While you probably can’t disable nltest.exe, looking for instances of it executing with a command line that includes /dclist:<domain>, /domain_trusts or /all_trusts has proven to be a very high-fidelity analytic for us to catch both Bazar (in this incident) as well as TrickBot (in past incidents). In fact, based on this overlap, it appears likely that Bazar may be reusing some code from TrickBot, which could lead to some confusion over which malware family is which.

Detection Opportunity 3: Enumerating domain admins with net group

We also saw the adversary attempting to enumerate Windows domain administrator accounts, a behavior that we commonly associate with ransomware operators. In particular, we find it useful to look for net group "domain admins" /dom and net group "domain admins" /domain.

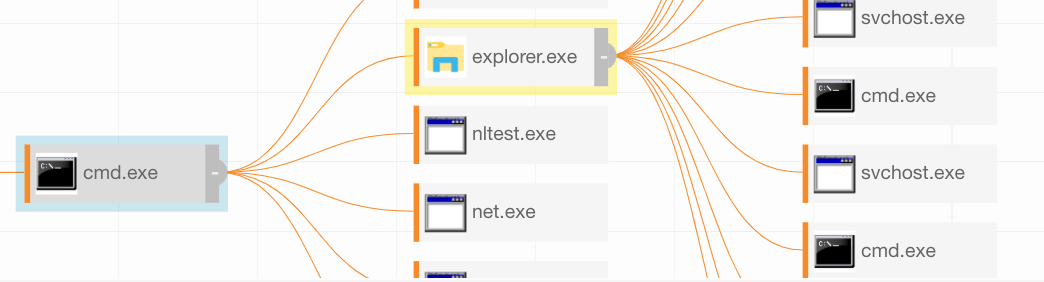

Detection Opportunity 4: Process hollowing of explorer.exe

During this phase, we also saw the adversary use process hollowing with both explorer.exe and svchost.exe. We observed explorer.exe spawning svchost.exe—this isn’t normal, so you should look for that in your environment. More broadly, you can look for svchost.exe processes where the parent is not services.exe to identify this and other malicious activity. (If you’ve never checked it out, we highly recommend looking at the SANS Hunt Evil poster!)

Another way we detected this activity was by looking for svchost.exe with no command-line options. Legitimate instances of svchost.exe should almost always have command-line options that include -k and the name of a service the process manages. Instances of svchost.exe with no command-line options are suspicious and may indicate that svchost.exe has been spawned to host injected code—like we saw in this incident.

Detection Opportunity 5: Attempted lateral movement via WMI + PowerShell + Cobalt Strike

Next, a Cobalt Strike binary was dropped on the endpoint as a .dll file and executed by rundll32.exe. With that, the intrusion began spreading laterally via Cobalt Strike. The operators used Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) in their lateral movement attempt. WMI spawned cmd.exe, which subsequently spawned PowerShell with an encoded command line. This encoded PowerShell creates another Cobalt Strike Beacon. We’ve found that looking for encoded PowerShell is a great way to catch this specific evil and a lot of other evil, too. In this incident, we saw a command line that began with:

powershell -nop -w hidden -encodedcommand JABzAD0ATgBlAHcALQBPAGIAagBlAGMAdAAgAEkATwAuAE0AZQBtAG8AcgB5AFMAdAByAGUAYQBtACgALABbAEMAbwBuAHYAZQByAHQAXQA6ADoARgByAG8AbQBCAGEAcwBlADYANABTAHQAcgBpAG4AZwAo...

Cobalt Strike uses the same structure for beacon payloads, consisting of an outer layer of Base64 encoding that contains within it another Base64 string, which is gzip-compressed. Once you’ve unzipped this compressed data you’ll see a more standard structure underneath. The string IEX $DoIt inside the gzip data is a dead-ringer that you’re looking at Cobalt Strike, but for quick detection purposes, looking for the entire string above in a command line can help you identify suspicious PowerShell activity. Along these lines, Florian Roth has a Sigma rule that is a great jumping-off point for hunting down suspicious encoded PowerShell commands.

If that’s too noisy in your environment, you could filter this analytic by looking for just powershell.exe that is a child of cmd.exe and a “grandchild” of wmiprvse.exe.

Detection Opportunity 6: Lateral movement via Cobalt Strike’s SMB PsExec module

We then observed successful lateral movement using Cobalt Strike’s SMB PsExec module. services.exe executed the previously-dropped Beacon payload with a child process of rundll32.exe. rundll32.exe had no command line arguments and performed multiple network connections over SMB (TCP port 445) to other systems on the network. The admin$ share was used in each instance. To detect this the way we did, we recommend looking for rundll32.exe executing without any command-line parameters and also establishing network connections. Additionally, looking in the Windows System Event Log for events with ID 7045 could also give you the opportunity to detect this. Event ID 7045 records the creation of new Windows services and should occur whenever any PsExec-like lateral movement occurs.

Detection Opportunity 7: Enumerating enterprise administrator accounts

Next, we observed the adversaries enumerating enterprise administrator accounts. We recommend looking for the command line net group "enterprise admins" /domain, which we observed in this incident, and also helps us catch other malicious activity.

Detection Opportunity 8: Credential access using lsass from regsvr32

We then observed the adversaries obtaining credentials. We aren’t sure whether they were using Mimikatz, but we can say they used an lsass cross-process from regsvr32.exe, which is something that Mimikatz is known to do. One way we detect Mimikatz SEKURLSA::LogonPasswords execution from any process is by identifying common lsass.exe process access mask values used by Mimikatz in conjunction with the loading of five or more of the following DLLs associated with credential operations:

- Logoncli.dll

- Samlib.dll

- Vaultcli.dll

- Cryptdll.dll

- Wintrust.dll

- Wkscli.dll

- Netapi32.dll

- Hid.dll

- Apphelp.dll

- WinScard.dll

Additionally, we found that simply looking for regsvr32.exe making external network connections, as well as regsvr32.exe execution without command-line options, helped us detect this activity. As is the theme with many of these detection opportunities, these same analytics have helped us detect a lot of other evil in the past too.

Detection Opportunity 9: Bloodhound execution

Around the time of regsvr32.exe execution, the operators also executed Sharphound or Bloodhound (we aren’t sure which) as code injected into regsvr32.exe. This tool performs a massive amount of reconnaissance of networks hosting Windows systems to find privileged accounts to target. We often detect Sharphound/Bloodhound activity by hunting for many SMB connections over port 445 originating from a single process. Bloodhound produces many more port 445 connections in large network environments, so it’s easier to spot in network traffic in larger environments as compared to smaller environments. If you’re in a smaller environment, you might have to tune this more based on the normal volume of SMB activity in your network.

Detection Opportunity 10: Adfind extracting information from Active Directory

Less than an hour after the initial execution, we observed the operators downloading and executing `adfind.exe` for reconnaissance purposes. adfind.exe is an open source tool that extracts information from Active Directory. You could try looking for any use of adfind.exe—or disallowing it from your environment completely—but if that’s too noisy, here’s the specific commands we saw used that you could detect on:

AdFind.exe -f "(objectcategory=computer)"

AdFind.exe -f "(objectcategory=group)"

AdFind.exe -f "(objectcategory=organizationalUnit)"

AdFind.exe -f "(objectcategory=person)"

AdFind.exe -subnets -f "(objectCategory=subnet)"

AdFind.exe -sc trustdmp

AdFind.exe -gcb -sc trustdmpWe know, that’s a lot. In under an hour, we saw all this activity . . . and detected it! We were fortunate that the initial access activity was detected within minutes, as preventative controls were ineffective and the adversary was moving fast. We immediately notified the customer and our mutual incident response partner, Kroll. Acting swiftly, Kroll began executing response processes including isolating endpoints and banning malicious binaries, as our CIRT continued to publish detections for the escalating lateral movement and credential theft. When the dust settled, the customer was left with nothing more than the set of detections that we escalated, documenting the progression of the threat. Thankfully, there was no ransomware at the medical center that day.

What you should do now and if an infection occurs

Beyond behavioral analytics that might help unearth potentially malicious activity in your environment, there is also a long list of proactive and reactive security controls that may help block a ransomware infection—or limit its effects—in the first place.

Be prepared ahead of time

Some things to consider before you’re facing a ransomware infection include the following:

- Make sure you are maintaining updated operating systems, software, and firmware.

- Maintain backups of important information and have a plan for recovering from backups. It’s important to periodically test your ability to recover from backups. This will help validate your recovery plan and also ensure that your backup data isn’t corrupt or otherwise unrecoverable.

- Periodically review domain administrator and accounts that have access to admin shares across your environment.

- Validate email security gateway policies and consider configuring them to quarantine and review documents or archive files before releasing them.

- Educate users so that they exercise caution when opening documents and following links, especially when they come from an unexpected sender.

- Have a disaster recovery and business continuity plan in place, and use this as an opportunity to review it.

- Consider keeping an incident response partner on retainer. These firms handle ransomware response on a daily basis and can provide invaluable assistance that could limit the impact of an outbreak and vastly expedite the recovery process.

- Also consider investing in third party assessment services like penetration testing to periodically evaluate the efficacy of your security controls and tools that afford you the ability merge extensive detection and response capabilities.

Be ready to act quickly

Once you are aware that something might be awry, act quickly:

- Isolate or quarantine any endpoints that you suspect might be infected immediately. Unplug them if you need to—this could be critical to making sure further activity doesn’t happen.

- If you have an IR partner, call them immediately. If you don’t, then consider calling an incident response firm as soon as possible.

- Ban malicious artifacts such as suspect IP addresses, domains, and hashes as soon as you become aware of them.

- Start disconnecting services from the network.

- Consider turning off non-critical IT systems.

- If you have Windows file servers, you can use features built into the File Server Resource Manager to alert on and fight ransomware. Within FSRM you can create file groups and policies to alert administrators when certain file names or extensions appear within Windows file shares. With a specific configuration, you can create a “crypto canary” on your file servers to notify you when Ryuk or other families encrypt file shares. Depending on how your shares are structured in terms of departments, users, and groups, you can target your response accordingly and visit victim computers to remove them from the network.

Additional Resources

From Red Canary

- https://redcanary.com/blog/ryuk-ransomware-attack/

- https://redcanary.com/blog/its-all-fun-and-games-until-ransomware-deletes-the-shadow-copies/

- https://redcanary.com/blog/detecting-and-mitigating-ransomware/

- https://redcanary.com/blog/cybersecurity-resources-for-schools/

From the Community

- DHS alert from Thursday, October 28: https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/alerts/aa20-302a

- The DFIR Report blog posts, which discuss very similar patterns to what we have observed: https://thedfirreport.com/2020/10/08/ryuks-return/ and https://thedfirreport.com/2020/10/18/ryuk-in-5-hours/

- Mandiant blog post covering KEGTAP (also known as Bazar) and other malware families they have recently observed: https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2020/10/kegtap-and-singlemalt-with-a-ransomware-chaser.html

- SANS webcast about UNC1878, a group Mandiant has recently observed deploying Ryuk, featuring Aaron Stephens and Van Ta from Mandiant and hosted by Red Canary’s Director of Intelligence, Katie Nickels: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BhjQ6zsCVSc

- Indicators of Compromise for UNC1878 released by Mandiant: https://gist.github.com/aaronst/6aa7f61246f53a8dd4befea86e832456

- Cybereason blog post on Team9 and Bazar: https://www.cybereason.com/blog/a-bazar-of-tricks-following-team9s-development-cycles

- Kroll recommendations on ransomware preparedness: https://www.kroll.com/en/services/cyber-risk/assessments-testing/ransomware-preparedness-assessment

- CrowdStrike post about WIZARD SPIDER and Bazar: https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/wizard-spider-adversary-update/

- Vitali Kremez post: https://www.vkremez.com/2020/04/lets-learn-trickbot-bazarbackdoor.html

- Lares blog post on endpoint hunting in Splunk: https://www.lares.com/blog/endpoint-hunting-for-unc1878-kegtap-ttps/

- Joe Slowik’s collection of suspected Ryuk domains: https://pastebin.com/UQs0JtKY

Brian Donohue, Katie Nickels, Paul Michaud, Adina Bodkins, Taylor Chapman, Tony Lambert, Jeff Felling, Kyle Rainey, Mike Haag, Matt Graeber, and Aaron Didier contributed to this blog post.