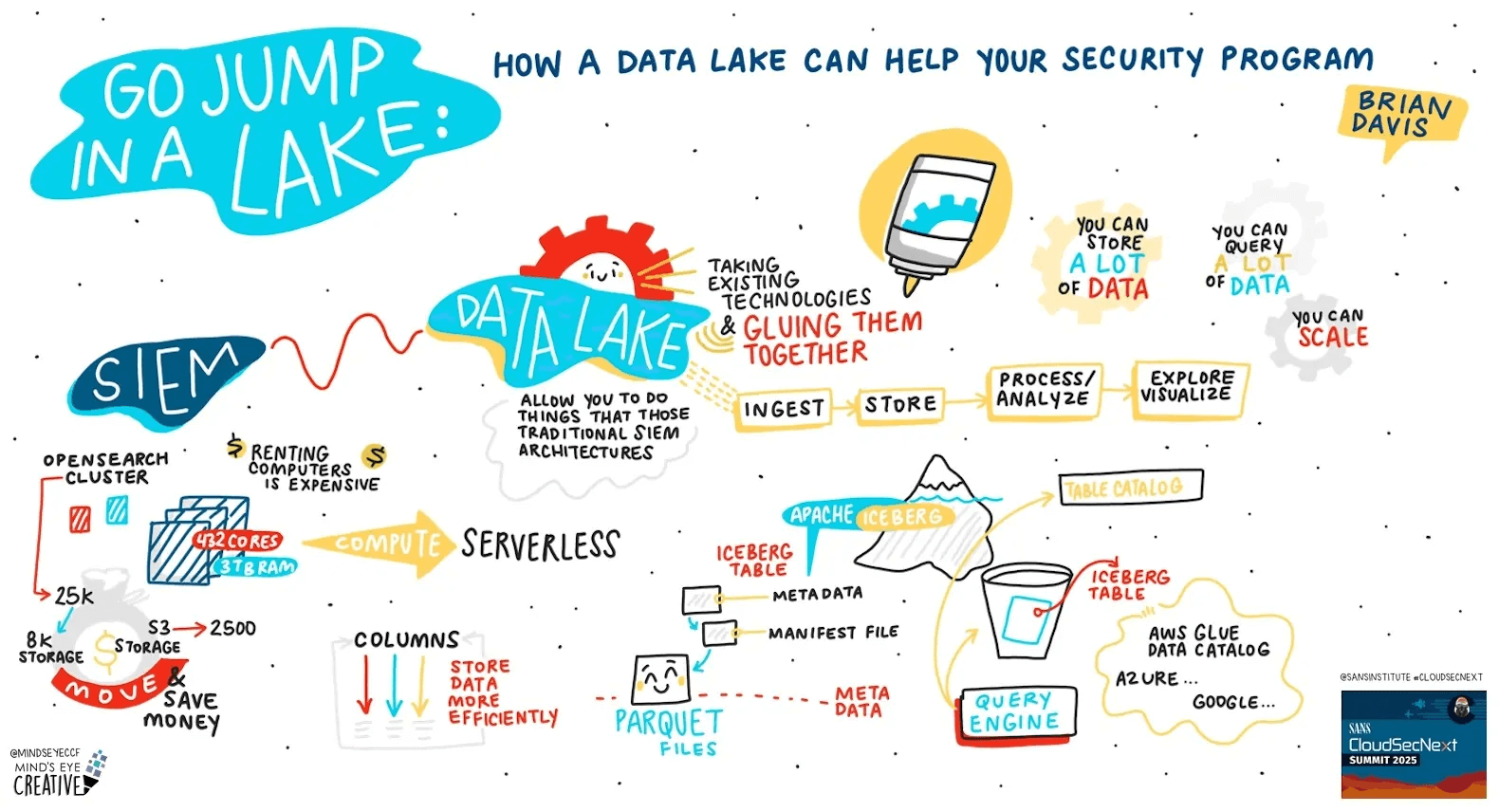

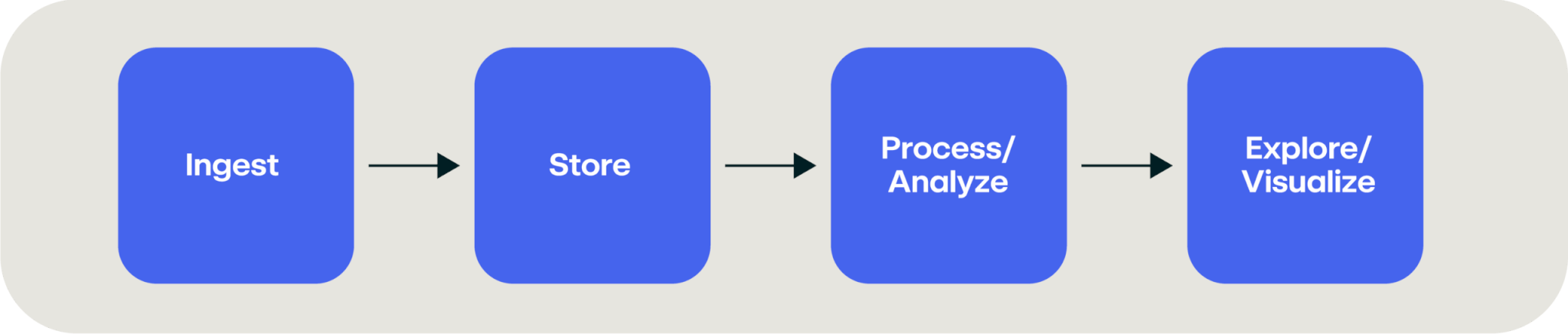

In part one of this series, we touched on some of the cost challenges associated with storing data in a SIEM and explained what a data lake is and how they can help shave down some of those costs. If you need a quick refresh, here’s a handy visualization from my talk on data lakes at SANS CloudSecNext 2025:

Illustration by Ashton Rodenhiser

Admittedly, I’ve done a lot of hand waving up to this point. I magically made storage become object storage and I made it so that the expensive servers can become serverless functions; so it’s time to talk about how this magic actually happens.

But first I’m going to talk about comma-separated values (CSV) files.

Getting your ducks in a row, and then in a column

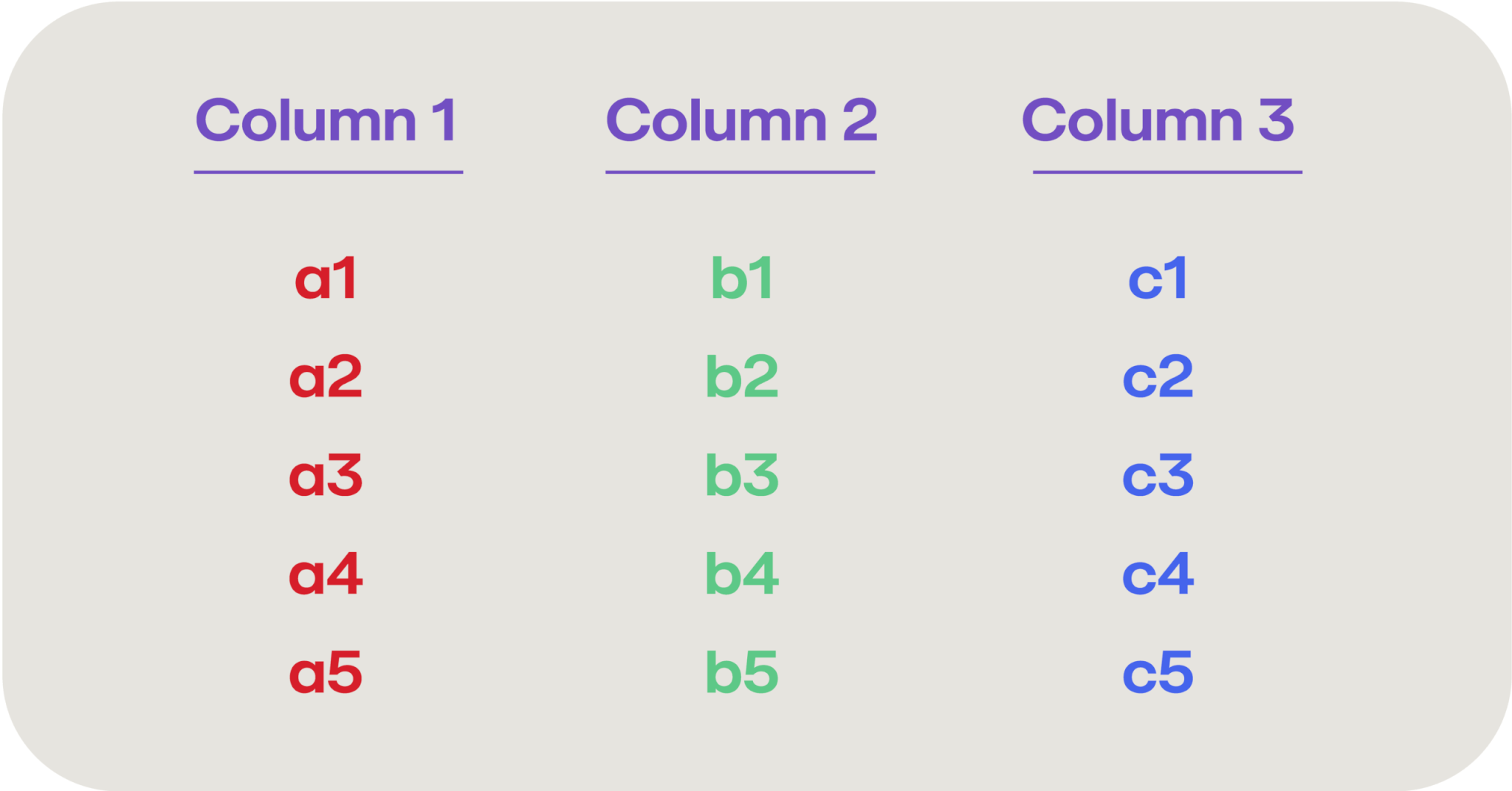

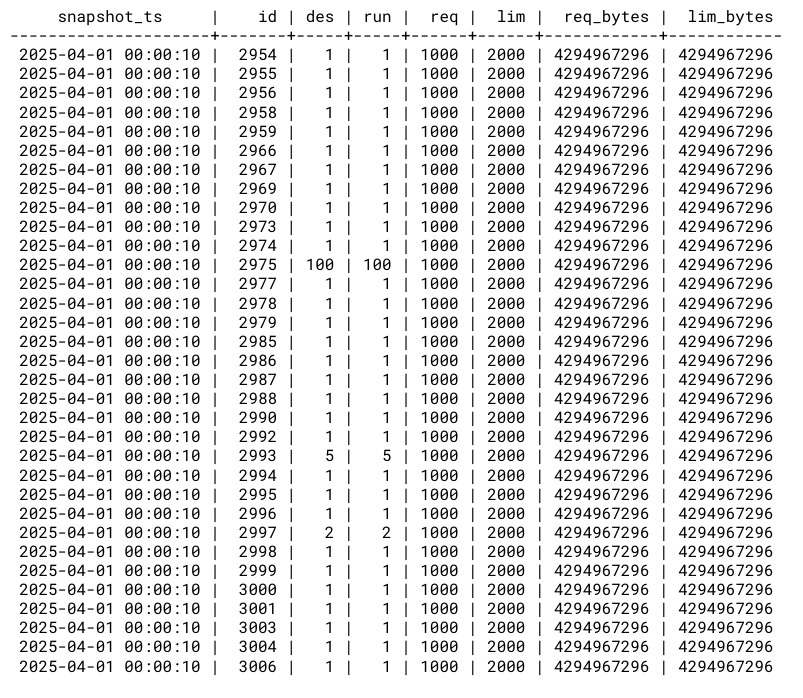

The data entered into a SIEM is typically some form of log records, usually related to events occurring within your IT environment. These log records are then parsed out into their constituent fields, essentially turning into a database row with several different columns (such as device, timestamp, severity, event, etc.). So your SIEM log data may look something like this:

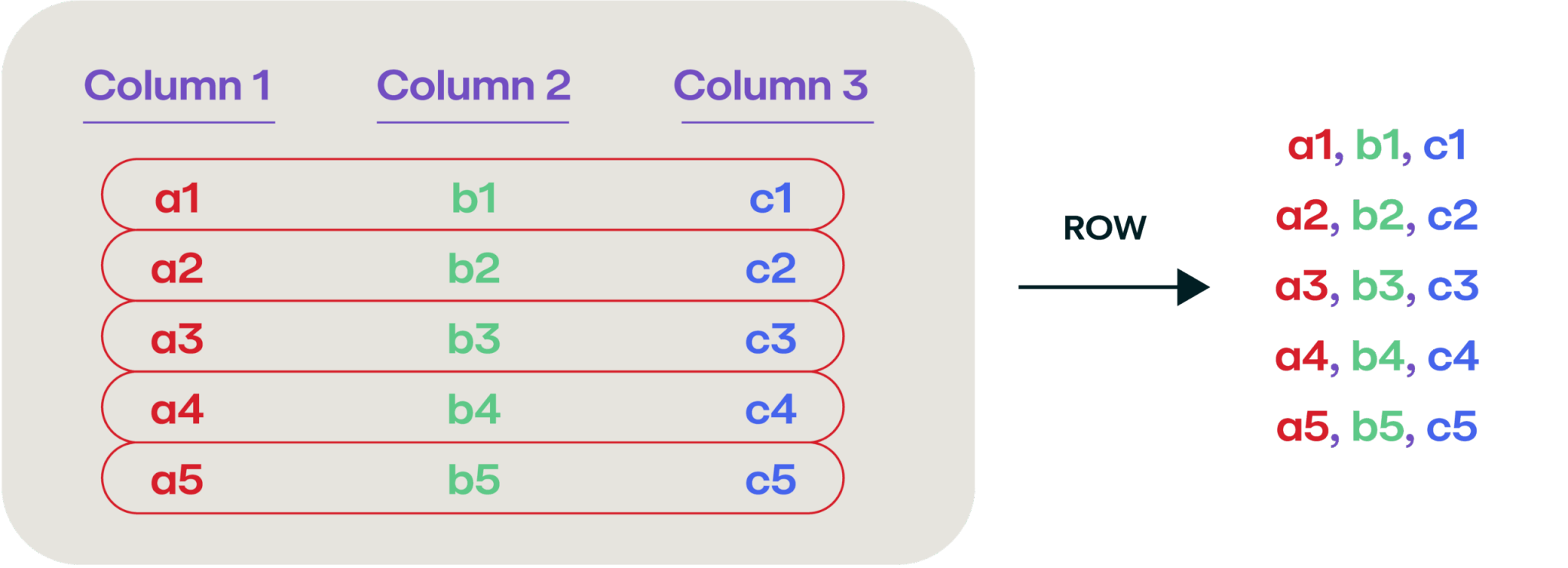

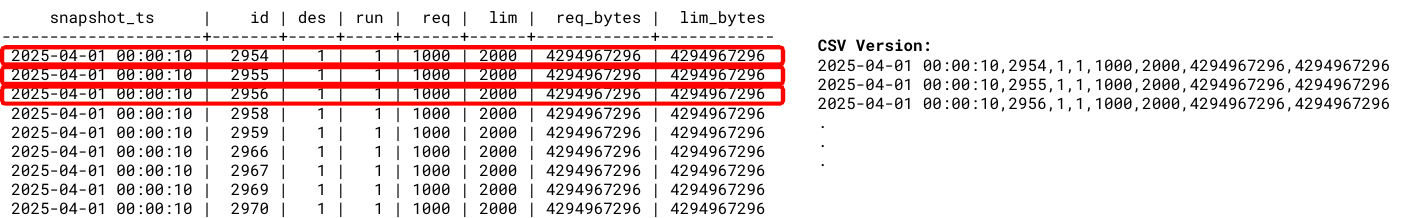

We usually think of saving this type of tabular data as a CSV file where we enumerate each column in each row, and write them out separated by commas, like this:

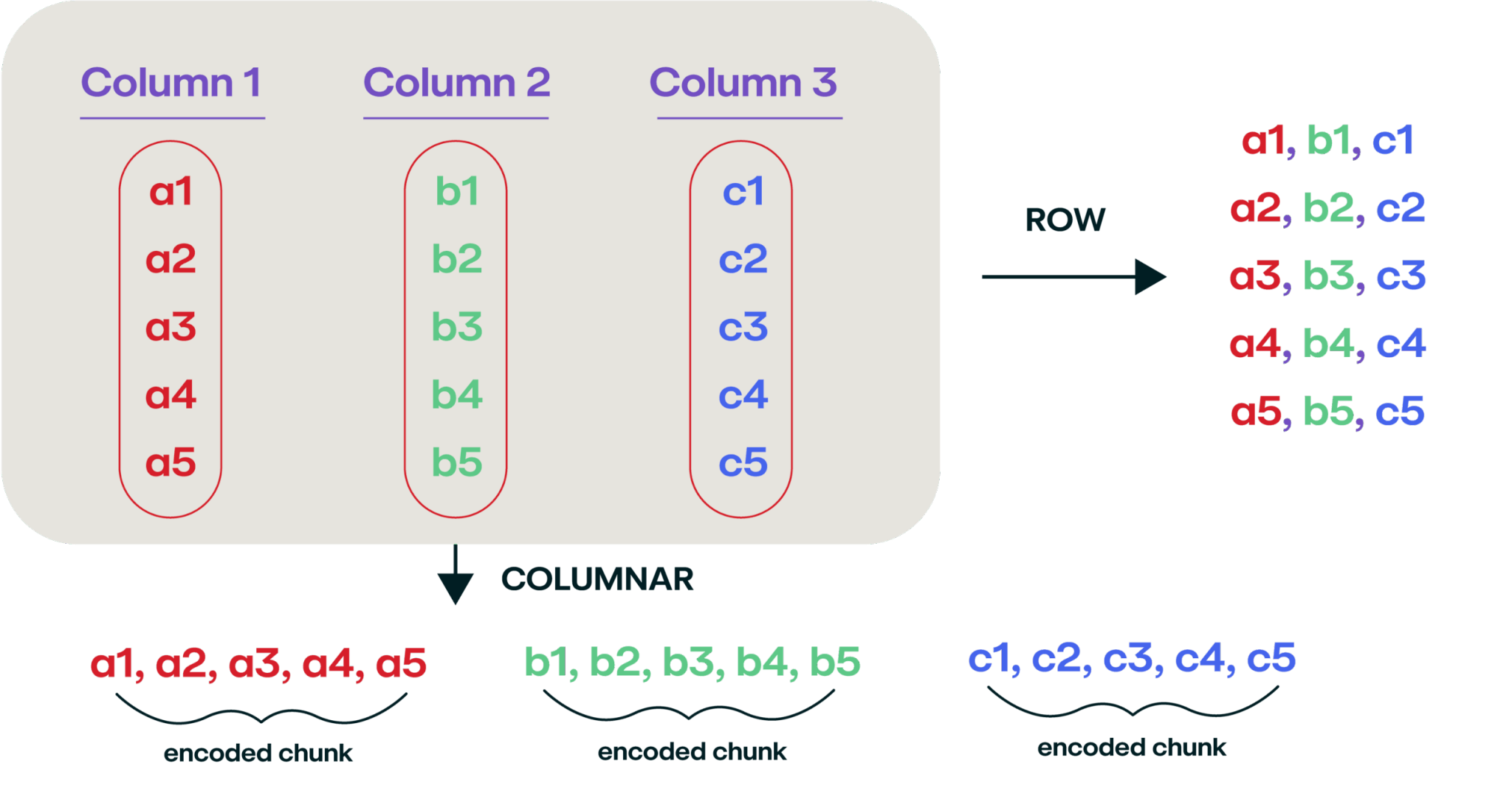

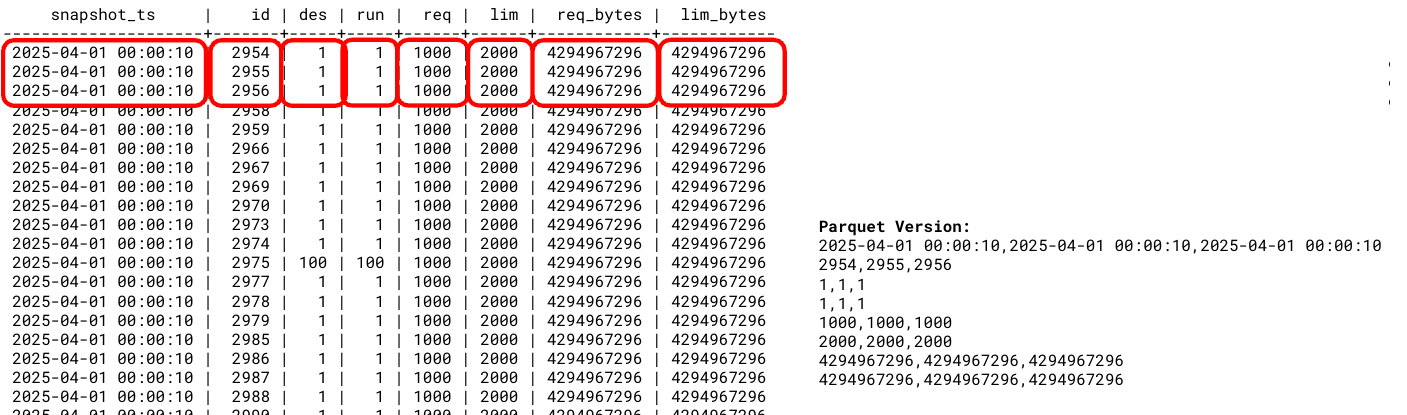

But, it turns out that storing data this way is really inefficient if you’re storing a lot of it, and a better way to store the data is in a columnar format. This isn’t a new and novel way of storing data (the idea was first introduced back in 1985). Instead of reading the data left to right, enumerate it over each column:

Let me give you a more tangible example. Here’s a table of some data gathered on April 1, 2025:

If you were to output this as a CSV file, it would look (intuitively) about the same:

But now, what if we output it in a columnar format (one of which is called Parquet):

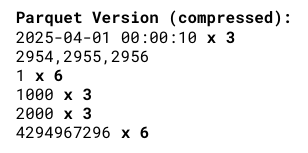

The real magic of writing data in this way is the immediate compression you can gain just by saying “you know what, the date 2025-04-01 00:00:10 repeats six times, and then I’ve got some unique numbers, then the number 1 repeats six times.”

Ultimately, this data table (which has 5 million rows) was the following sizes:

- CSV file: 290 megabytes

- Gzipped CSV: 24 megabytes

- Parquet: 8.8 megabytes

You can start to see the benefit of this file format from a storage standpoint. Additionally, it’s a lot easier to search for a specific value in a certain column, as those columns are all co-located on disk next to each other This is why most online analytic processing (OLAP) databases store data in a columnar format.

The tip of the Iceberg table

If we decide to store all of our incoming SIEM log data in a columnar format, that starts to offer some fast searchability as well as significant storage savings. And using those serverless compute instances, we could write a handful of records to a Parquet file whenever we received them, then power back off. Over time, we’d have a Parquet file filled with our data records, and we’d need to create another Parquet file, which introduces a challenge: “Which file has my record?”

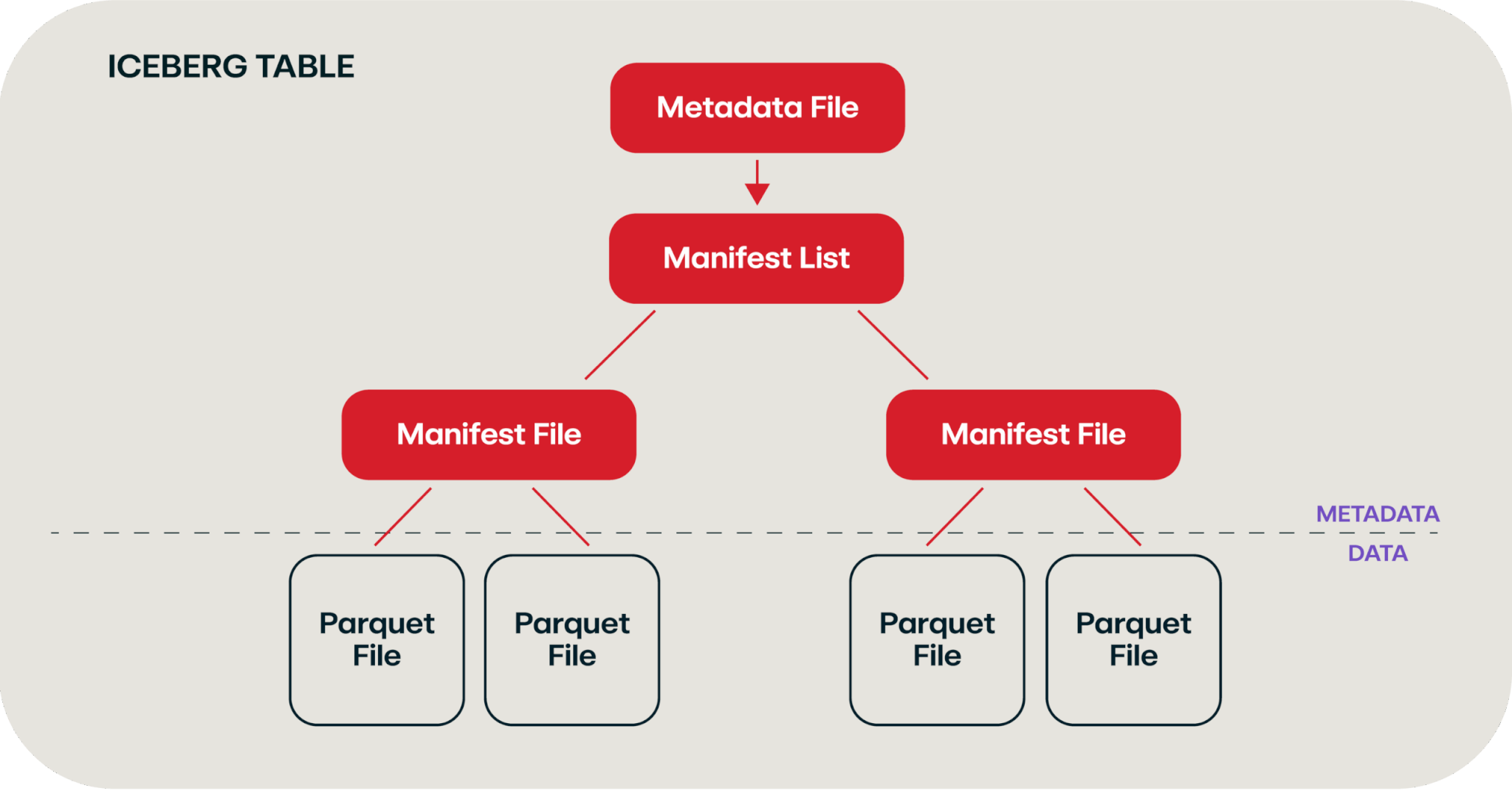

We solve that by creating a manifest file that contains a record of each of your Parquet files. Over time, you end up with a file hierarchy that looks something like this:

Chart adapted from this video and this blog

This hierarchy of files is called an Iceberg table, which leverages the Apache Iceberg standard. The neat thing about this standard is that this “table” allows for natural schema evolution (i.e., adding more columns over time), partitioning, time travel (via snapshotting), and atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability (ACID) compliance—all through a pile of files that we write to an object storage system. (While we use Iceberg in this example, it’s worth noting there are other competing file formats out there that serve similar purposes, such as Delta Lake or Apache Hudi.

The Iceberg table is one of the key foundations of the data lake—remember data lakes? This is a blog about data lakes. We can now write out data in a searchable fashion without those beefy SIEM servers running 24/7.

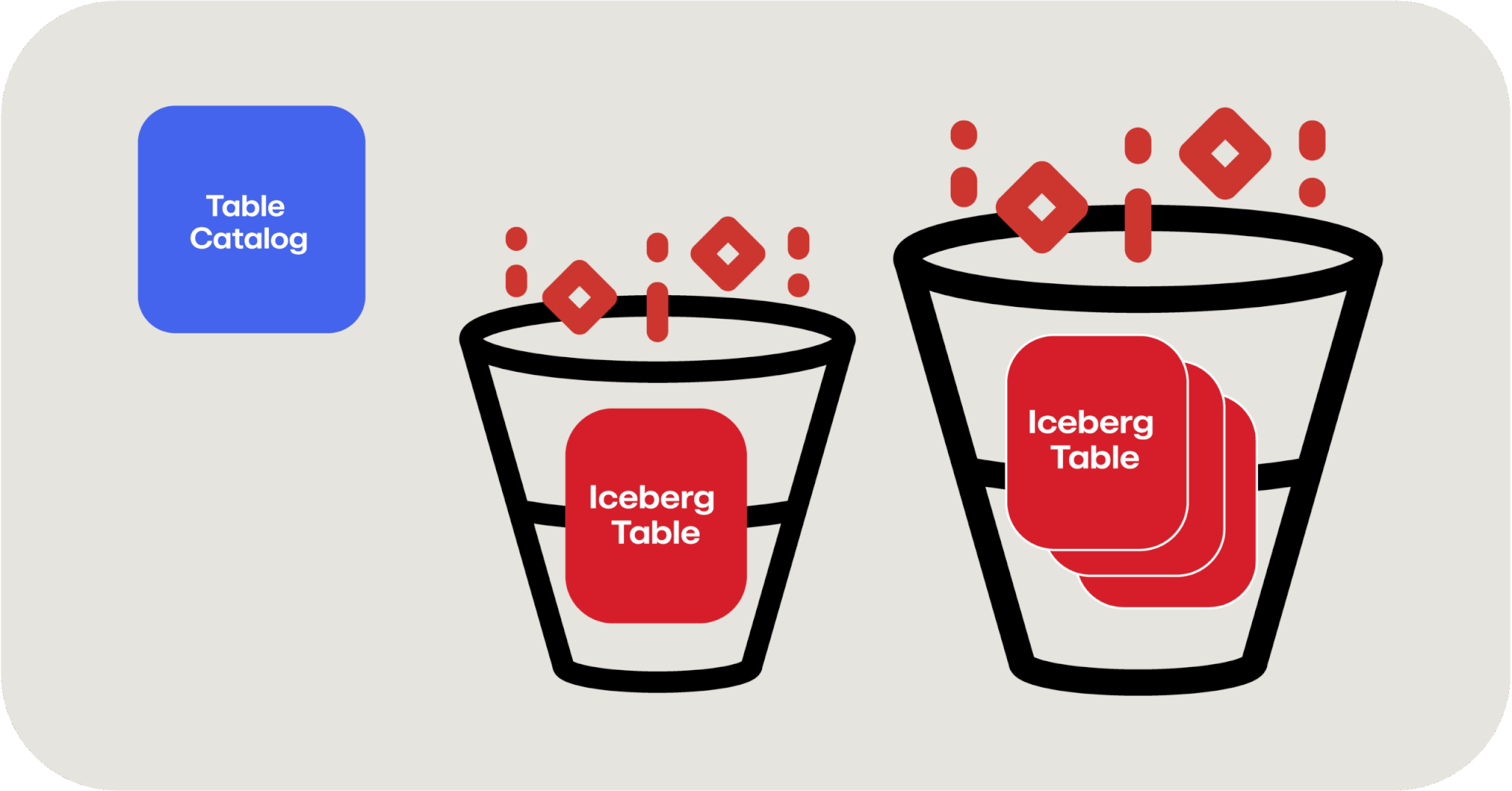

The next piece of the puzzle, in addition to the stack of manifest files and lists that we discussed previously, is a table catalog. We need a place to go that knows about all the various Iceberg tables we’ve written in the different buckets or blob stores. You can leverage an open source tool such as Apache Hive here or use a cloud provider’s data catalog tool like AWS Glue Data Catalog or Azure Data Catalog.

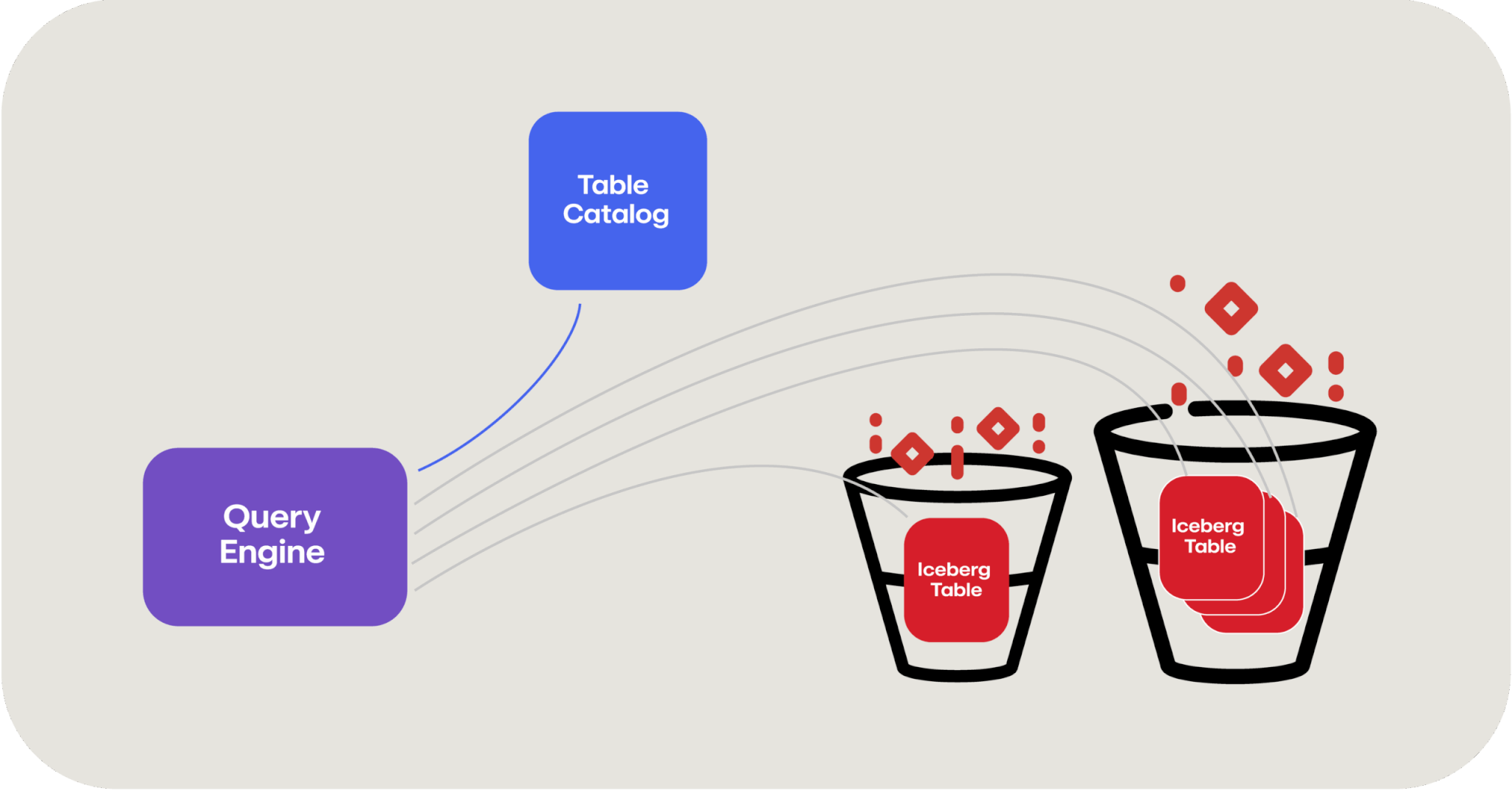

The last piece to fall into place is a way to query this data, and this is where our old friend Apache Spark comes into play. Apache Spark is a distributed data processing framework that natively knows how to reach out and query these Iceberg tables, leveraging a table catalog to do so. And because this is a distributed framework, it can leverage those serverless compute functions that we talked about before to quickly leverage as many computers as you need to query data in parallel.

In this manner, querying a data lake can actually be faster than querying a database because you have the advantage of decoupled storage and compute and therefore, in theory, an unlimited amount of computing horsepower to apply to the searching of data.

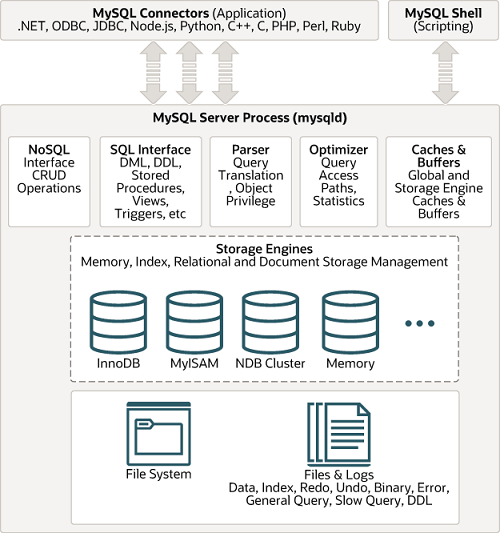

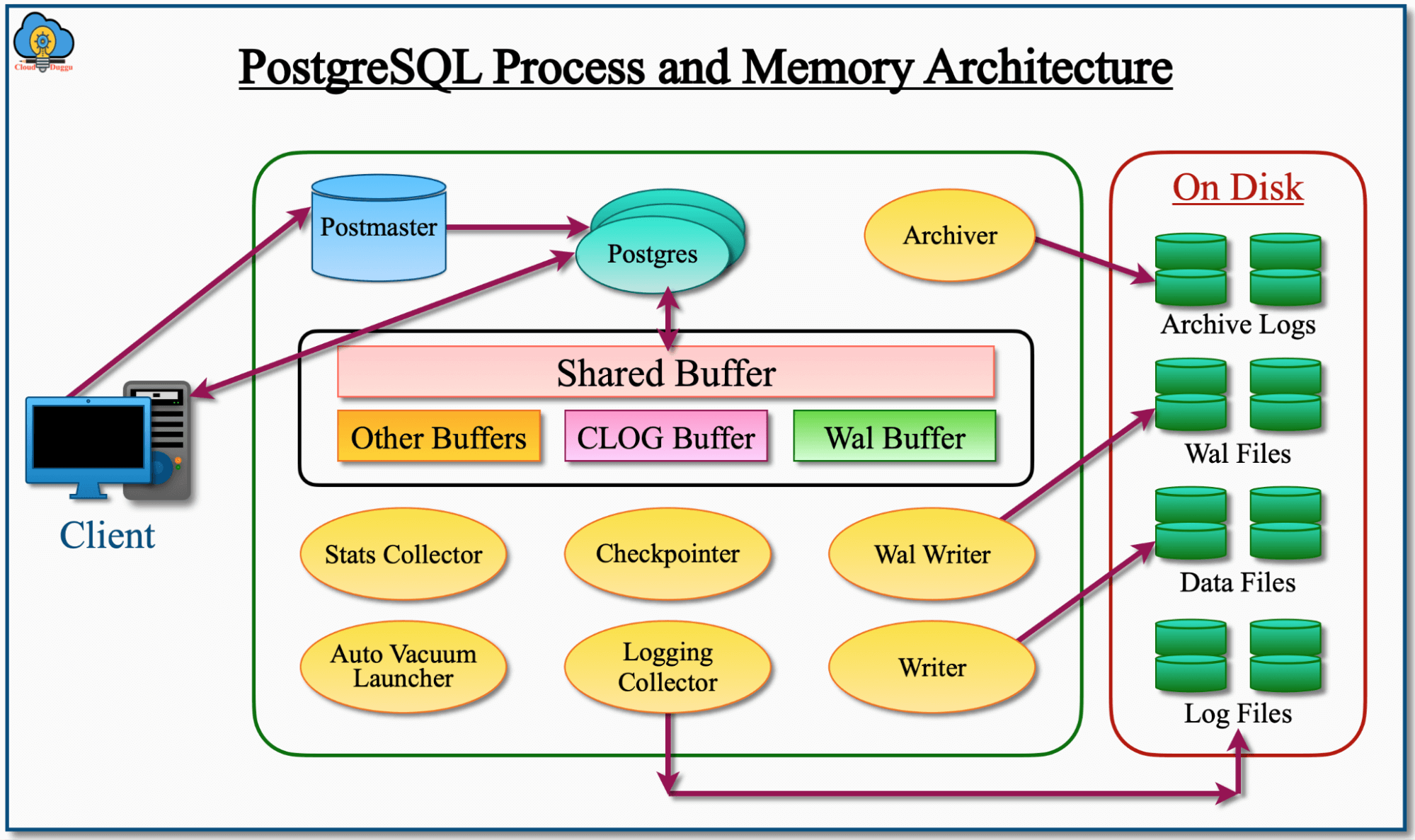

“If you’re looking at all of this and scratching your head saying, ‘I don’t get it. This seems too complicated’—it kind of is.” But I’d also assert that you’ve probably never looked at the internal architecture diagrams of a MySQL or PostgreSQL database before, see below, which is arguably just as complex. A data lake is effectively just building a database from first principles: storage, catalogs, and tables.

Image courtesy of MySQL documentation

Image courtesy of CloudDuggu

So, where does this leave us?

- A data lake allows you to store a massive amount of data very inexpensively since it leverages cloud object storage (and can take advantage of cold storage such as Glacier as well)

- You can query a LOT of data: Queries are federated across as much compute as you want to spin up to query thousands of files within a cloud object store (which is itself incredibly scalable)

- You can easily scale; you’re not limited by any constraints of storage or compute

Speaking of scaling, here are some statistics on Netflix’s data lake from TrinoFest 2024, a conference held annually around the open source, distributed structured query language (SQL) engine Trino:

- 1+ exabyte of data

- 3 million Iceberg tables

- Largest Iceberg table is 36 petabytes

- Ingests 10+ petabytes per day

- Deletes 9+ petabytes per day

- 600 commits per second

- 500,000 queries per day

- 2,500+ unique users

Data lakes allow you to do things that simply aren’t practical or cost effective in a traditional SIEM due to the fundamentally different architecture under the hood.

But there’s a catch. (There’s always a catch)

Unlike a SIEM, where you are paying a fixed cost for a fixed capacity, a data lake’s costs are bounded only by how much data you store, how much preprocessing you might want to do on the data as it’s ingested, and how much data is scanned on query. This is purely a consumption based cost model, which is great if you don’t query the data very much, but can surprise you if you go to pull back lots of data and see a surprise $2,000 AWS Athena charge on your next AWS invoice.

Building a data lake for fun and profit

So, now that we’ve demystified what a data lake is, you’ve decided you want one of your own. You can absolutely go out and just buy one (I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Red Canary has one) or you can decide you want to build one of your own.

There are four key phases of a data lake to consider when building it out:

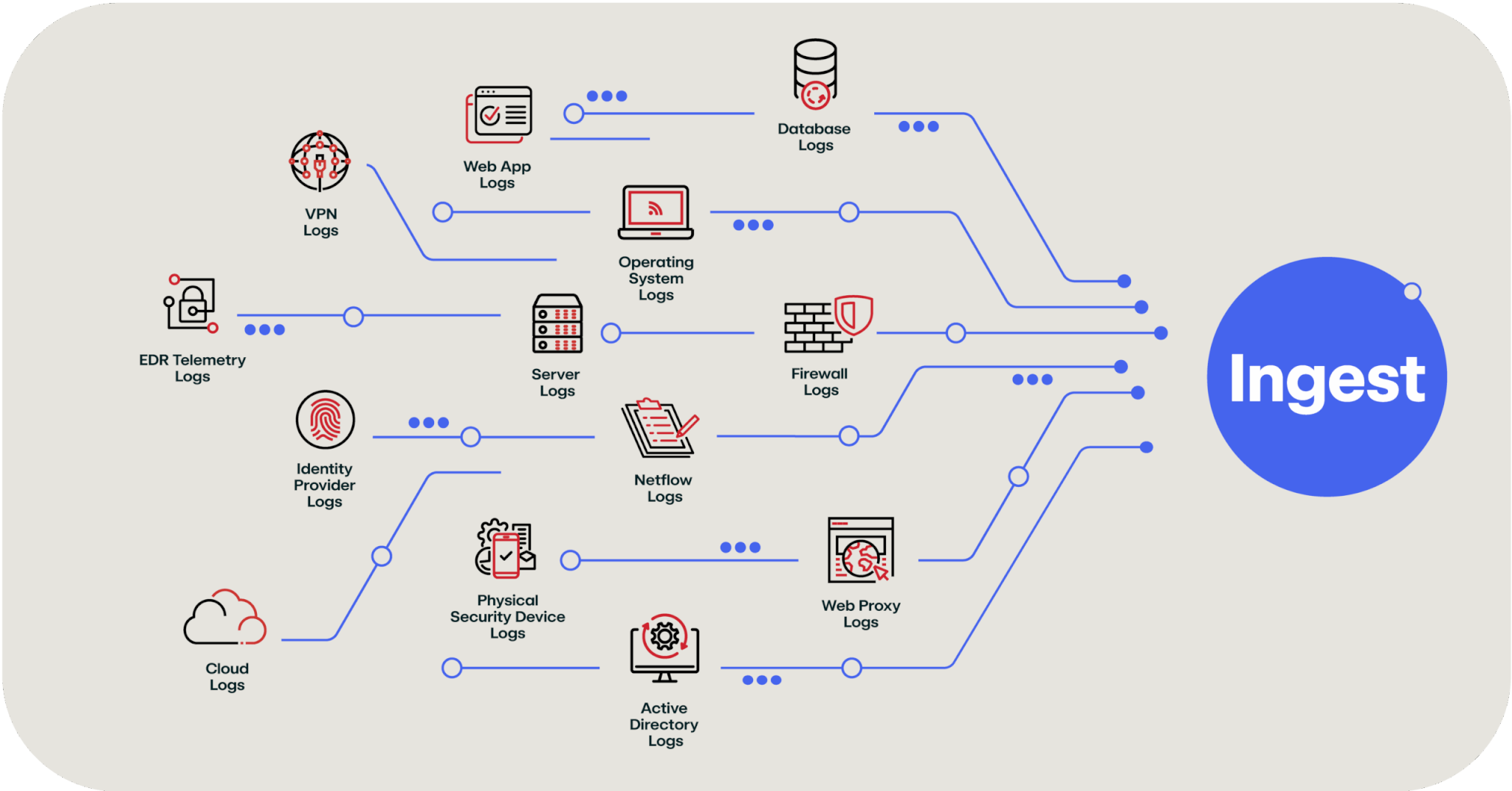

Ingest

Ingest covers how you’re going to get all of your data IN to the data lake. One of the challenges of the data lake concept is that it is mostly focused around artificial intelligence (AI) and data science applications; so if you Google “ingest data into my data lake” you’re going to find a bunch of articles about extract, transform and load (ETL) jobs, and other data science-related discussions. But if you’re a security practitioner, you’re going to want something more like this:

The above image breaks down the firehose of SIEM or SIEM-adjacent data that needs to get pushed into a data lake. The good news is that every major cloud provider has tools to make this easier:

There are also lots of other commercial and open source tools like Cribl, Fivetran, and RedPanda Connect that specialize in moving data from one thing to another thing, including a data lake.

Store

Storage is the easiest part in the entire process; if you leverage a cloud provider’s object storage, the Apache Iceberg (or whatever your preferred table format) data storage just sits as files on top. Each cloud provider offers data lake optimized storage as well to improve performance of the writing and queries of this data:

Process/Analyze

This section could probably warrant another several blogs so instead I’m simply not going to do it justice and just list out several tools that you can leverage to process, query, and analyze the data:

- AWS Glue

- Amazon EMR

- Amazon Athena

- Azure Synapse Analytics

- Azure Databricks

- Google Cloud Dataflow

- Google Dataproc

- Google BigQuery

- Apache Spark

- Apache Flink

- Trino

- Presto

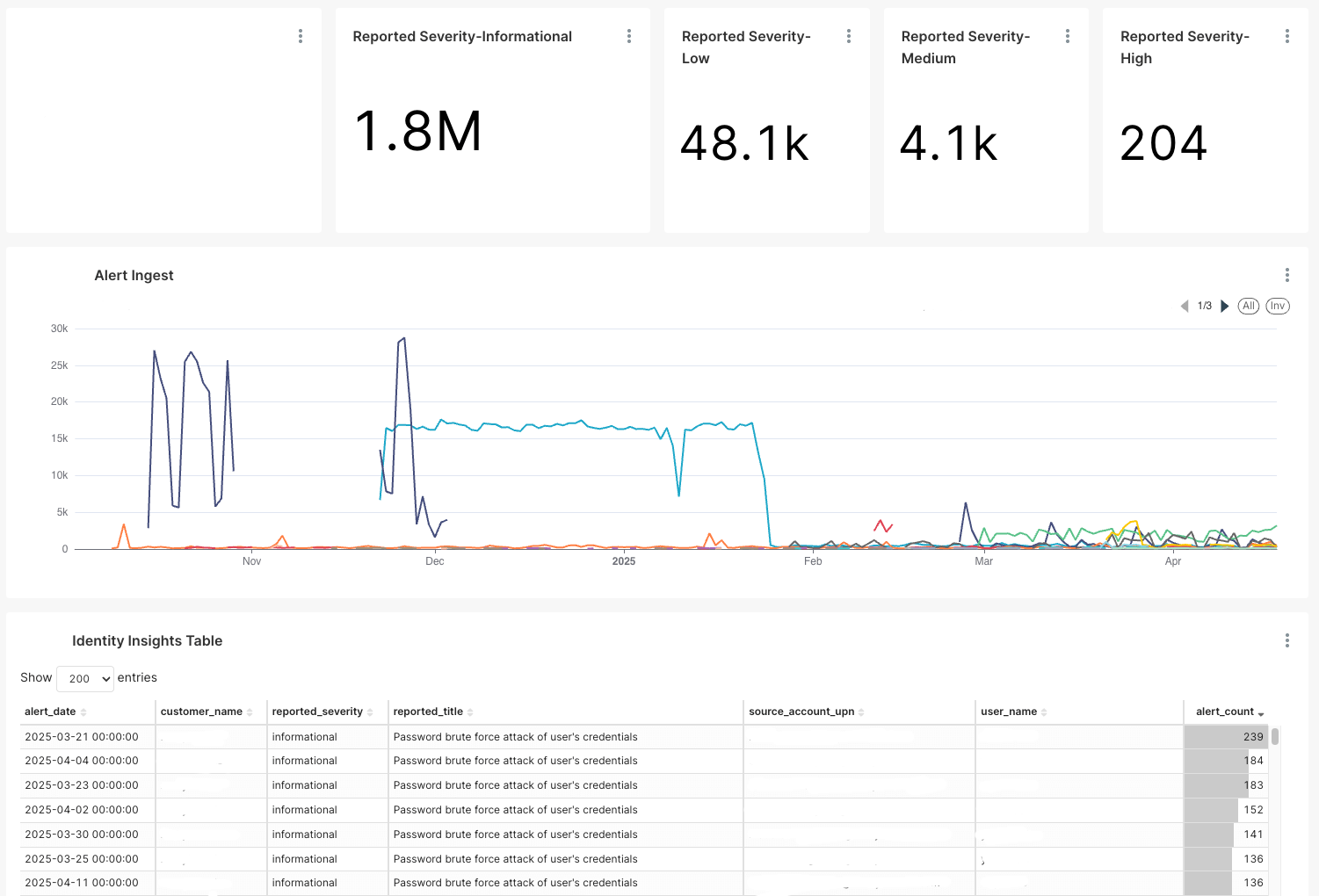

Explore/Visualize

One of the powers of a SIEM is the ability to create rich dashboards and visualizations. This is far more useful than looking at raw logs. The good news is that several tools enable this same rich exploration of the data in your data lake (and more seem to be appearing all the time):

Below are some examples of the types of visualizations you can get using Apache Superset.

Example 1:

Example 2:

And the best part is that these dashboards (and all the other data) are queryable using a normal SQL query such as this (again—three raccoons just pretending to be a database):

SELECT

date_trunc('day', CAST(created_at AS TIMESTAMP)) AS created_at,

severity AS severity,

count(severity) AS "count(severity)"

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM data_lake.bronze_detections

WHERE source IN ('autodrafted_by_toolA', 'autodrafted_by_toolB')

AND state NOT IN ('rejected', 'draft')

) AS virtual_table GROUP BY date_trunc('day', CAST(created_at AS TIMESTAMP)), severity ORDER BY "count(severity)" DESC LIMIT 10000;Security use cases for data lakes

An important call out here is that a data lake is not going to replace your SIEM but instead act as a cost effective augmentation to the tooling you already have. So what are the security use cases?

Too much data

This use case is for “all your other data.” You probably want to collect and store more data than you can afford today and you have to drop a lot of valuable context information on the floor that would help your security operations (SecOps) team do their job better or easier. Adding a data lake to your SIEM allows you to keep this data for as long as you want in a very cost effective manner, supplementing your SIEM for investigations.

Trends over time

Once you can store more data and perhaps retain it for longer than you could afford to in your SIEM, you can start to look for long term trends over time that weren’t visible before.

Write once, read never

We all have data retention requirements where we need to store data for long periods of time that no one will likely ever use, but you need to prove to an auditor (or yourself) periodically that you still have it. This is a perfect use case for a data lake that leverages extremely inexpensive cold storage (like Amazon S3 Glacier, where that 105 terabytes would cost us $100 per month to store).

Machine learning and AI

If you haven’t already dipped your toes into machine learning or AI, a data lake is a perfect data source for these tools. There’s a reason why Apache Spark, which provides the necessary framework for processing petabytes of data, is the bedrock of a lot of AI infrastructure now.

What next?

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about how a data lake works and the technology building blocks that can be used to assemble a data lake. The value it provides is extremely inexpensive long-term storage that’s still surprisingly quick to query and search. These building blocks are also likely already within reach of your organization if you’re already using a cloud provider—or you can reach for a turn-key solution like Red Canary’s Security Data Lake. Either way, the value of a data lake can quickly pay for itself if you’re using more expensive solutions today.