Grief is a combination ransomware-extortion threat that first emerged in May 2021. The group behind Grief maintains a public leak site where it posts stolen victim data. Despite the handful of attacks publicly attributed to Grief, there’s been very little technical intelligence published about the ransomware and the precursor behaviors that precede it.

Red Canary’s visibility into this threat has been limited, but—through a series of short-term incident response engagements—we’ve noticed certain conspicuous patterns in the malicious activities leading right up to the point of encryption. We haven’t seen the initial infection vectors nor—importantly—the actual process of files getting encrypted. However, we’ve seen the aftermath of the encryption and many of the behaviors that come before it. We also performed dynamic analysis on a Grief sample in order to get a better idea of what happens during the encryption process.

In this report, we’re going to share technical intelligence on how we’ve detected precursor activity and helped customers respond to Grief outbreaks over the last couple months.

The link between Dridex and Grief

Grief often turns up in environments where there’s been a Dridex infection and in which there’s evidence of the post-exploitation tool Cobalt Strike. Though we were unable to definitively determine that Grief originated from Dridex and Cobalt Strike in the environments we examined, we assess it’s likely that these environments were initially compromised via a Dridex infection and that the adversaries, in turn, leveraged Cobalt Strike and subsequently deployed Grief. This assessment is at least partially validated by Dell SecureWorks, which has also observed a relationship between Dridex, Cobalt Strike, and Grief. Just a few days ago, Zscaler published a report compellingly arguing that Grief is a rebranded version of the now inactive DoppelPaymer ransomware. This is important because DoppelPaymer has been a second-stage payload delivered after Dridex many times in the past, which further supports the idea that the Dridex activity we saw is related to Grief.

We published numerous strategies for detecting Dridex and Cobalt Strike in the 2021 Threat Detection Report. Those detection strategies continue to hold up, and, as you’ll see below, many of them helped us detect and respond to Grief incidents with our incident response partners.

Dridex

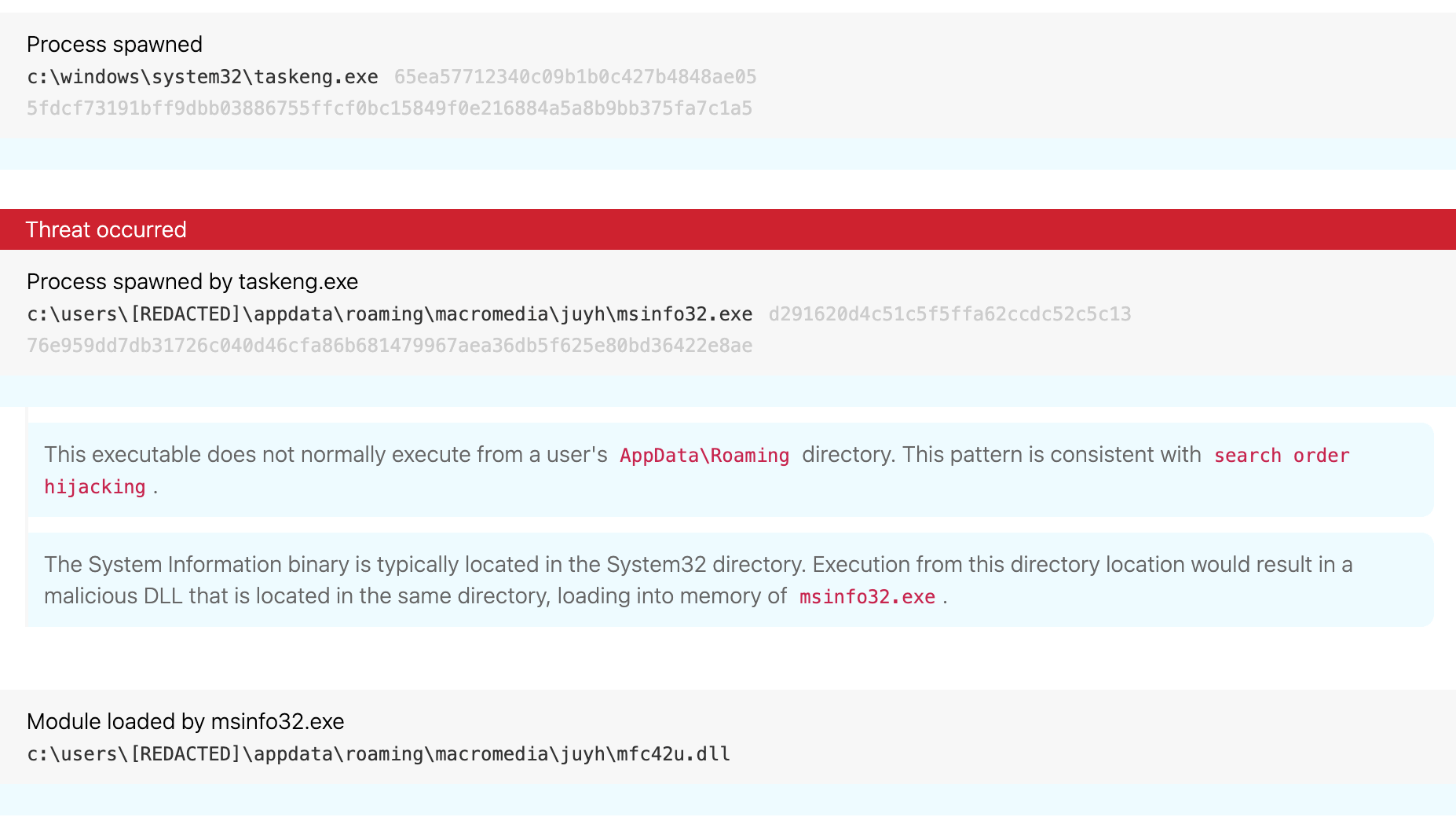

We’ve observed adversaries leveraging DLL Search Order Hijacking (T1574.001 Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Search Order Hijacking) when deploying Dridex in the leadup to a Grief infection. In general, this technique involves adversaries relocating native system binaries and executing them from a non-standard directory such as appdata\roaming. In cases where Dridex preceded Grief, we’ve seen adversaries relocate the system information binary (msinfo32.exe) to the appdata\roaming directory in order to load a malicious dynamic link library (DLL) into memory.

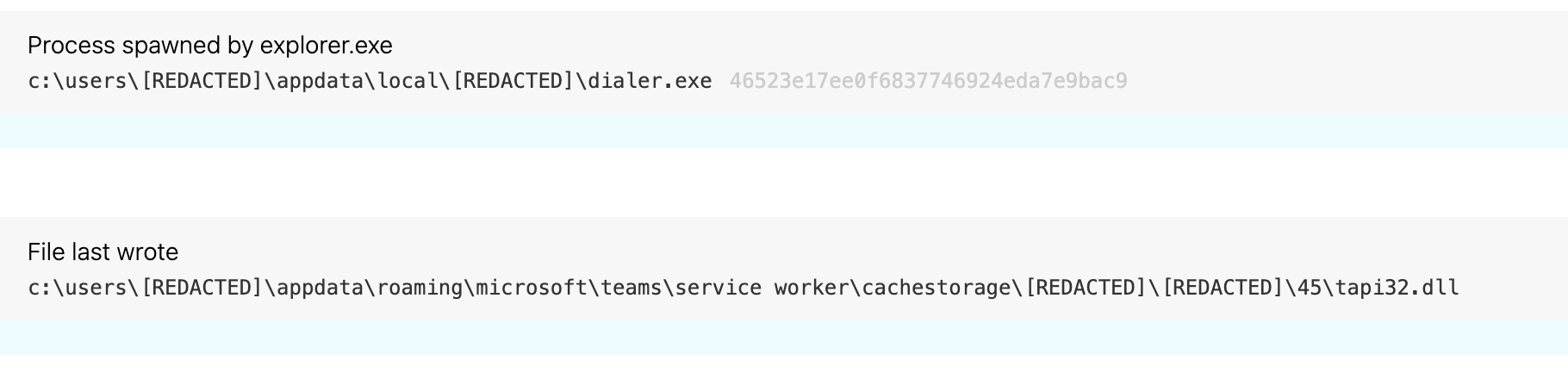

The following image represents a timeline of events on a single endpoint that illustrates what this behavior looks like in telemetry:

As you can see, the Task Scheduler Engine (taskeng.exe) spawns the relocated version of msinfo32.exe in the appdata\roaming directory. From there, msinfo32.exe loads a malicious DLL from the appdata\roaming directory that masquerades as a legitimate DLL (mfc42u.dll). (T1036.005 Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location)

Detection opportunity 1

As observed in the above telemetry, msinfo32.exe is executing without a corresponding command line, which gives us our first detection opportunity. Look for a parent process that appears to be taskeng.exe running in conjunction with a process path that includes users and appdata/roaming but without any corresponding command-line arguments.

Following that malicious DLL load, a cascade of different signed executables—almost always spawning from explorer.exe—launch from the appdata\roaming directory and load additional DLLs. Despite being named for legitimate DLLs, they too are malicious. In some cases, we’ve seen control panel (CPL) files instead of DLLs, but they serve the same functional purpose. The following image illustrates what this behavior looks like in endpoint telemetry, with the legitimate Windows dialer process (dialer.exe) loading a malicious DLL that’s been named to look like the telephony API client DLL (tapi32.dll).

Detection opportunity 2

Look for any processes executing from a non-standard directory or process path.

Following the example in Figure 2 above, you can look for the execution of a process that is dialer.exe from an non-standard process path.* Standard process paths may vary from one binary to another, but dialer.exe usually exists in windows\system32, windows\syswow64, or windows\sysarm32 directories.

*Note: This is easier said than done because you need to understand native Windows binaries and the file or process paths from which they are supposed to execute. Lucky for us, our colleague Shane Welcher and Michael Haag from Splunk already did the hard work of cataloguing the expected file path for every System32 binary (as well as other process metadata like internal binary names), on display in an article we published in early June. We consider that a foundational resource for anyone looking to bolster their coverage against DLL Search Order Hijacking and Masquerading, because it can help you develop methods for reliably detecting when binaries execute from non-standard file paths or directories or with unexpected file names. While it’s not tailored specifically to catch Dridex or other Grief-related activity, it will almost certainly help you develop better depth of coverage.

Some of the other binaries executing from non-standard directories include:

dialer.exe

systempropertiesperformance.exe

systempropertiesdataexecutionprevention.exe

systempropertieshardware.exe

sigverif.exe

computerdefaults.exe

tabcal.exe

wusa.exe

tpminit.exe

igfxsdk.exe

update.exe

The malicious DLLs and CPLs loaded by the above binaries include but aren’t limited to the following names:

mfc42u.dll

sysdm.cpl

wtsapi32.dll

version.dll

tapi32.dll

dpx.dll

Cobalt Strike

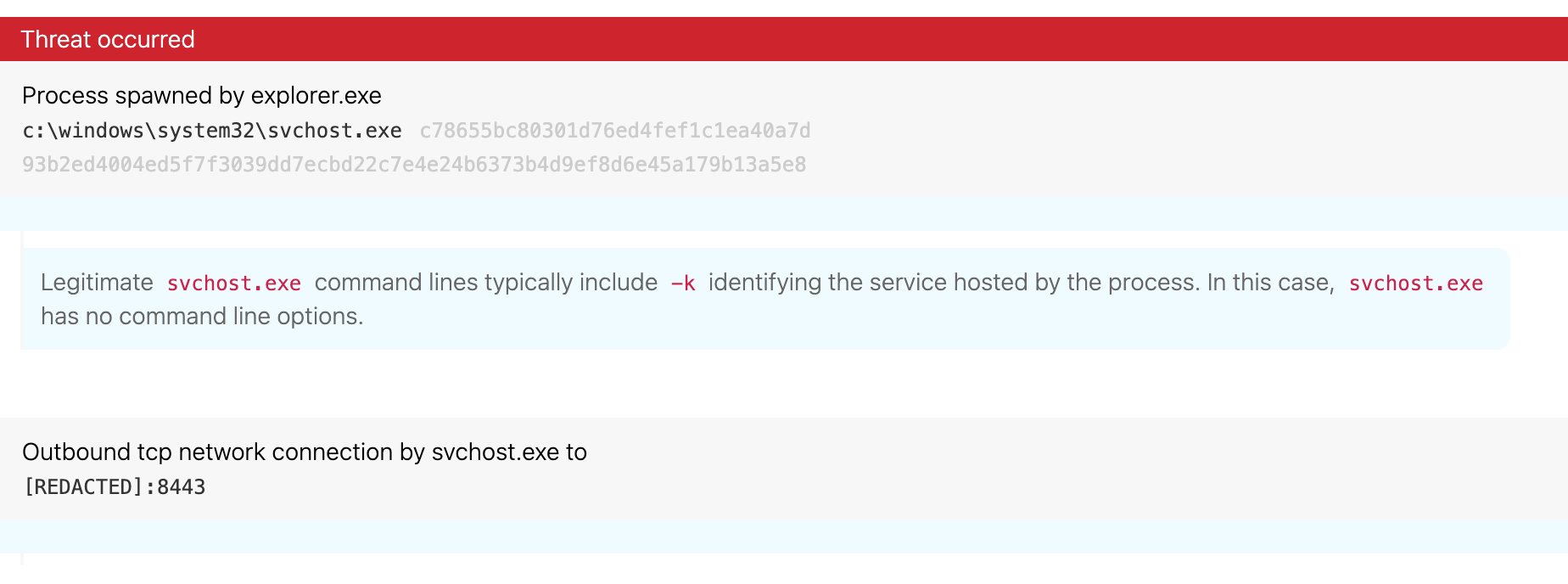

Cobalt Strike is one of the most common pre-ransomware payloads we observe, and it frequently follows malware families like Qbot, IcedID, or in this case, Dridex. In cases where Cobalt Strike precedes Grief, we’ve observed the Windows Service Host (svchost.exe) executing without any commands in the command line. Under normal circumstances, you’d always expect to see svchost.exe with a command line that includes the -k command and specifies a service group. As you can see in the following image, our detection included neither. This is likely the result of a Cobalt Strike Beacon injecting code into svchost.exe (T1055 Process Injection).

While we observed the adversary injecting into svchost.exe in this particular instance, Cobalt Strike often targets a variety of other system binaries for injection. From a high level, a Cobalt Strike Beacon injects code into memory by manipulating the memory space of a native Windows binary. When examining the telemetry associated with this behavior, we generally observe that the manipulated binaries execute without any corresponding command-line arguments. Importantly, if you take a step back and analyze what is normal activity for many of the system binaries abused by Cobalt Strike Beacons, it is not normal for them to execute without corresponding command lines.

Detection opportunity 3

Since it’s abnormal, alerting on the following processes when they execute without a command-line argument can be a good way to detect Cobalt Strike, whether it’s delivering Grief or serving some other malicious purpose:

rundll32.exe

werfault.exe

searchprotocolhost.exe

gpupdate.exe

regsvr32.exe

svchost.exe

msiexec.exe

To narrow this down even more, you can look for a process that appears to be one of these binaries executing without any corresponding command-line arguments and making an external network connection. You can see an example of this in Figure 3 for svchost.exe.

Bonus malicious behavior

During one of these intrusions, we also observed the Windows Print Spooler (`spoolsv.exe’) making an external network connection. While we aren’t able to associate this behavior with a specific threat (though we suspect it is related to Dridex), it’s nonetheless suspicious—and has helped us detect a variety of suspicious and malicious behaviors.

Detection opportunity 4

You can reliably detect this by looking for a process that is explorer.exe spawning spoolsv.exe along with an external network connection.

Grief counseling

All of this precursor activity leads up to the point where the Grief ransomware starts gathering permissions and encrypting files. We have not had great visibility into how Grief performs encryption, but we do have good insight into the activity directly preceding file encryption.

Getting permission

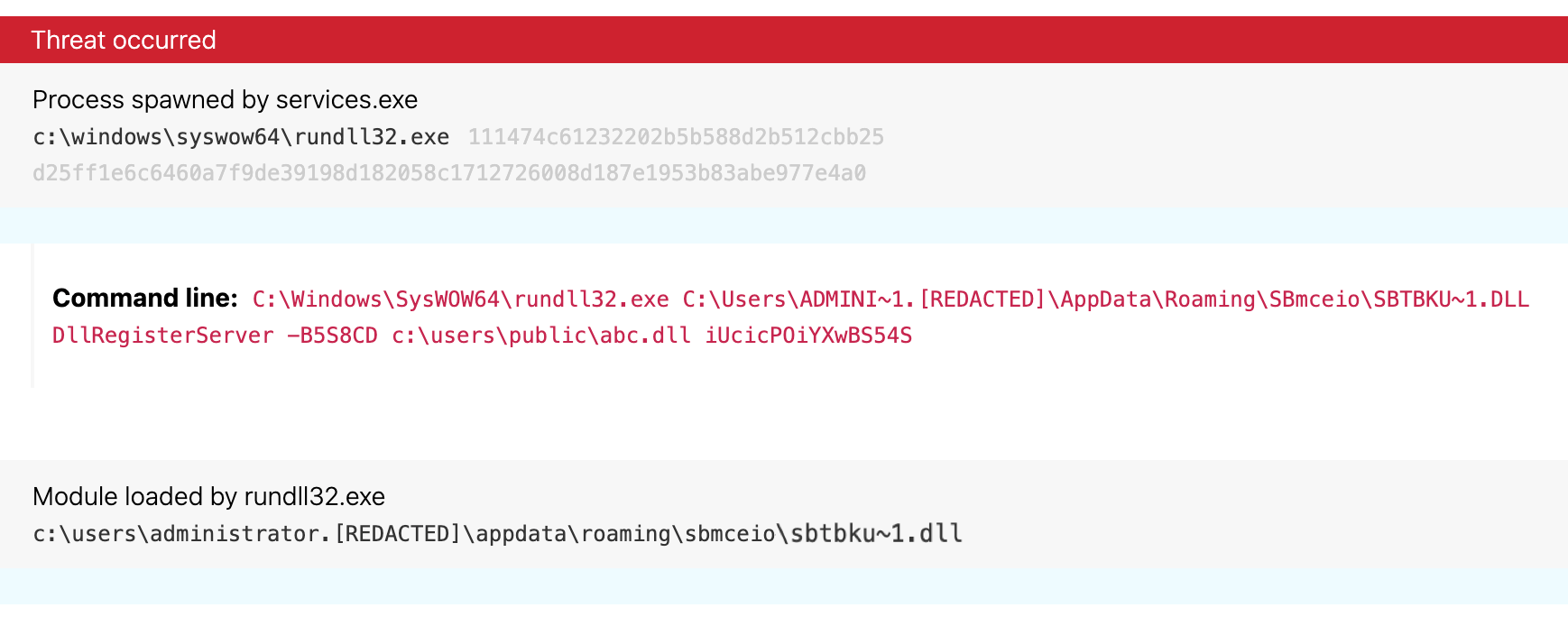

In addition to the Dridex and Cobalt Strike activity that we assess is related to Grief, we observed the Windows DLL Host (rundll32.exe) loading a malicious DLL (T1218.011 Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32). That DLL is arbitrarily named and performs a variety of functions. Based on dynamic analysis and process lineage, we assess that this DLL:

- created processes

- wrote registry values

- encrypted file contents

- modified Windows Services

- modified Windows boot options

- modified Windows Defender settings

- modified Windows filesystem permissions

In the Dridex section above, we described how the adversary used relocated executables to load malicious DLLs with legitimate names, thereby subverting the proper DLL search order in a technique known as DLL Search Order Hijacking. Here, the adversary is using rundll32.exe exactly as intended: to load and launch an arbitrary DLL. Of course, the DLL itself is malicious and kicks off a series of malicious events.

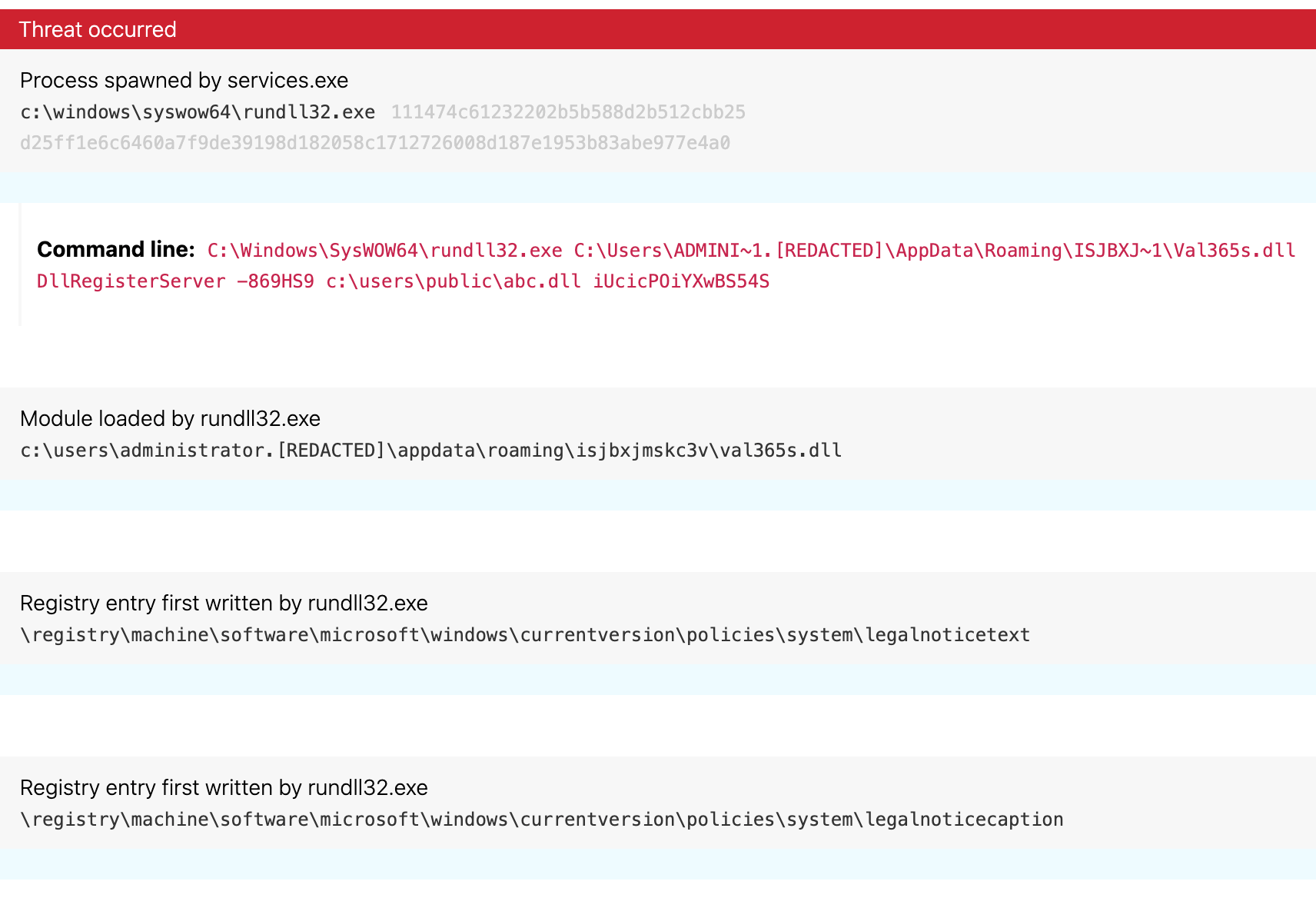

In the following image, you can see rundll32.exe running from the proper directory and loading a randomly named DLL, sbtbku~1.dll. In fact, the telemetry includes two DLLs. The payload is housed within the first DLL, sbtbku~1.dll. The purpose of anything beyond the DllRegisterServer function in the below command line is currently an intelligence gap, as we’re unsure the purpose it serves for the adversary. Note that when we removed either alphanumeric string (-B5S8CD or iUcicPOiYXwBS54S) or the trailing DLL (abc.dll) at the end of this command line, the malicious payload would not execute. If you have more info on this to help fill our gap, we’d love to hear from you!

Note: We renamed the above DLLs and strings because their names are arbitrary and some of them are unique to each affected endpoint. We have not determined why this is the case, but the DLL and random string in the front half of the command line (SBmceio\sbtbku~1.dll and -B5S8CD) changed from one endpoint to the next while the trailing DLL and random alphanumeric string (abc.dll and iUcicPOiYXwBS54S) remained constant.

Detection opportunity 5

As is illustrated in Figure 4, one way to detect Grief is by looking for the execution of a process that appears to be rundll32.exe executing with DllRegisterServer in the command line. This particular analytic is applicable to a wide variety of threats, including Qbot.

Similarly, you may also be able to detect this and other malicious activity by alerting on command lines that include DllRegisterServer and follow-on arguments, as is illustrated in Figure 4 and further below in Figure 7. The DllRegisterServer function, by design, is not supposed to implement parameters.

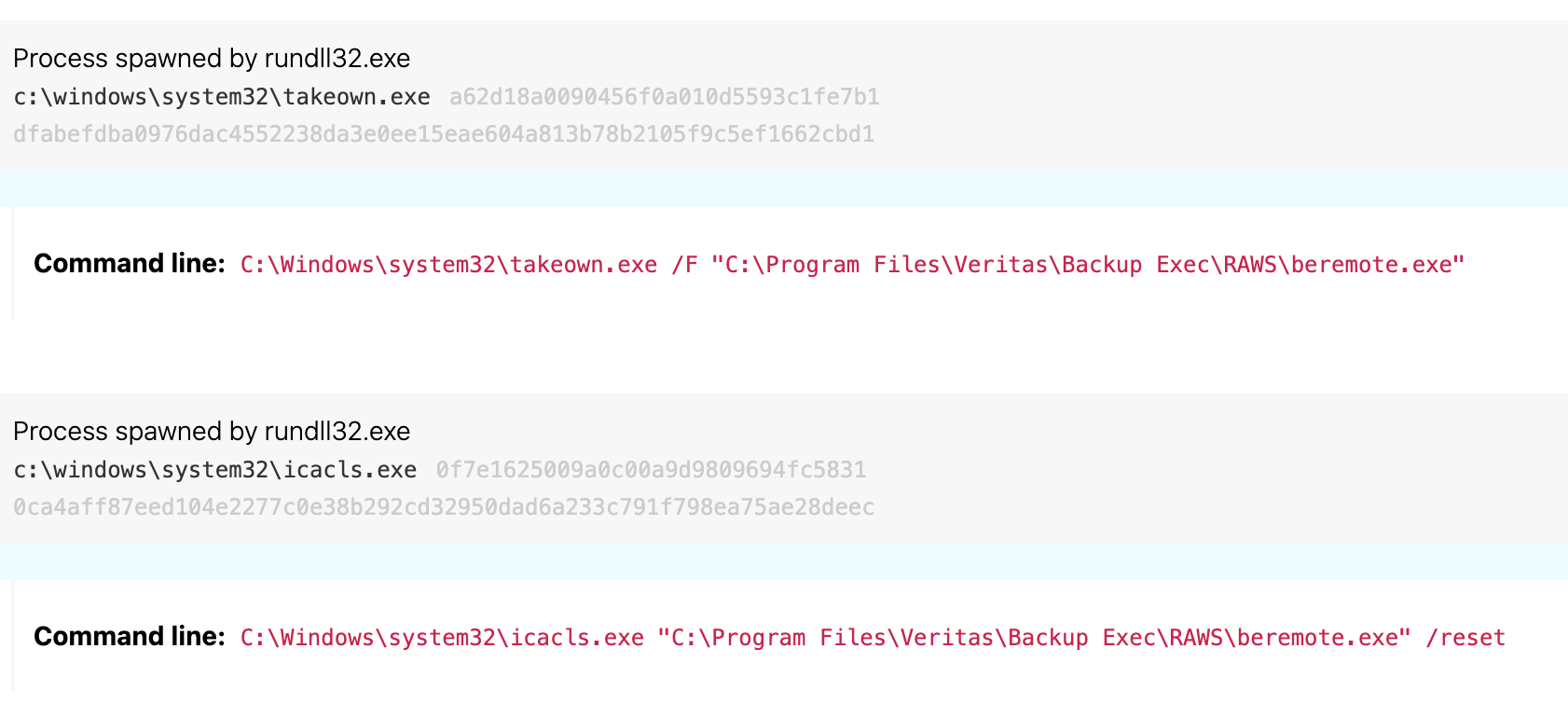

The first DLL in Figure 4 (sbtbku~1.dll) initiates multiple actions to facilitate encryption or manipulate backups. It launches a takeown.exe command that allows an administrator to take ownership of files relating to a backup, recovery, and data protection software called Veritas. It also launches an icacls.exe command that resets access permissions for the same files (T1222.001 File and Directory Permissions Modification: Windows File and Directory Permissions Modification). As the following image shows, takeown.exe and icacls.exe spawn as children of rundll32.exe because Rundll32 launched sbtbku~1.dll.

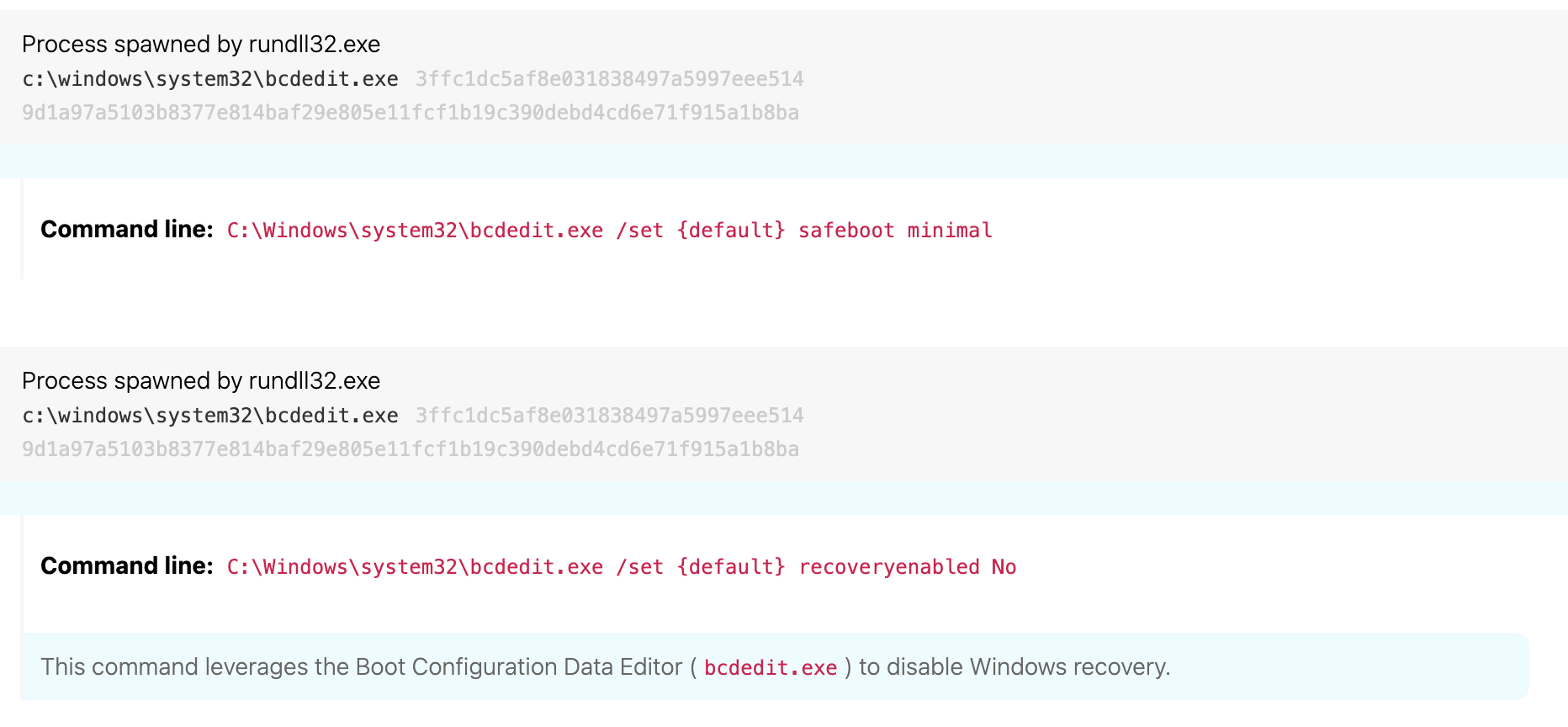

Last but certainly not least, sbtbku~1.dll launches the Boot Configuration Data Editor (bcdedit.exe) and uses it to set the default safeboot configuration for minimal functionality (preventing victims from accessing the internet, among other things) and to disable Windows recovery (T1490 Inhibit System Recovery).

Detection opportunity 6

The detection opportunity illustrated in Figure 6 is helpful for rooting out adversaries attempting to reconfigure Windows recovery settings. You can detect this by looking for a process that is bcdedit.exe spawning from a parent of rundll32.exe along with a command line containing “recoveryenabled” and ” no”.

Leaving a note

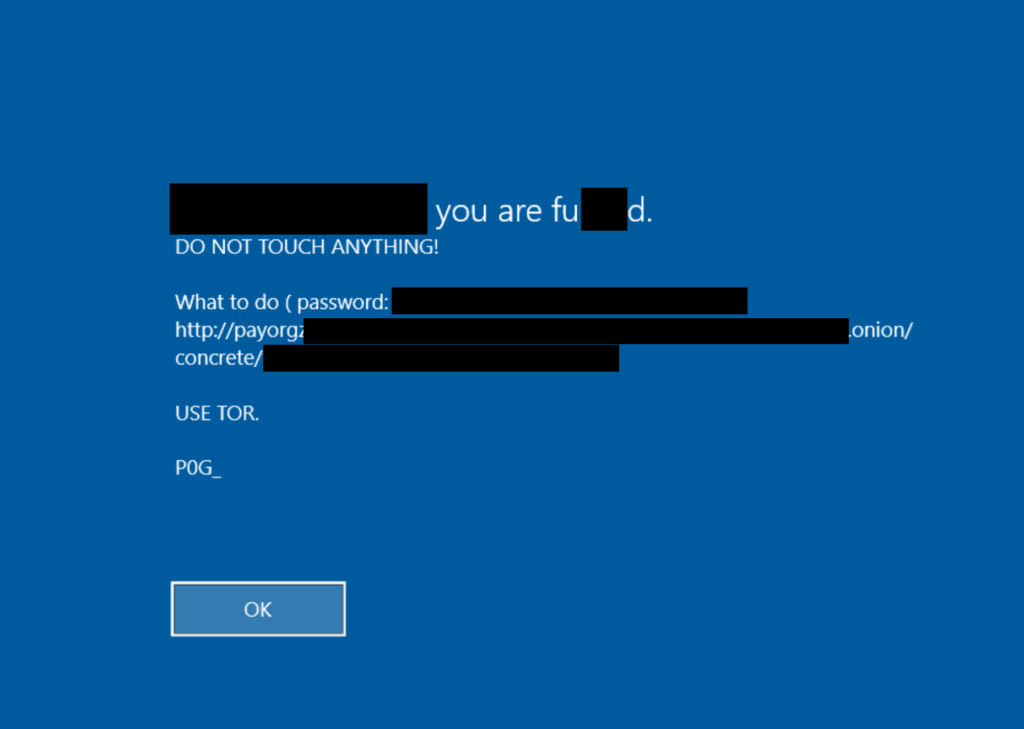

Interestingly, sbtbku~1.dll also modified the Windows LegalNoticeCaption and LegalNoticeText registry keys (T1112 Modify Registry), enabling them to display a ransom message customized to each victim environment immediately at logon.

The following image (Figure 8) shows how the manipulated Windows LegalNoticeCaption and LegalNoticeText registry keys displayed a ransom message customized to each victim environment. Under normal circumstances, these are the registry keys that IT administrators often use to display legal warnings at bootup on corporate-owned computers (e.g., “This computer is property of [company name]. Everything is monitored.”).

Additional observations

We received a sample of Grief from a third-party incident response partner and confirmed it was in fact Grief ransomware based on the .payorgrief file extension, the fact that the ransom linked to a known Grief TOR site, and the graphic in the ransom note. Our dynamic analysis of this sample helped us confirm much of the analysis above, along with the following additional observations:

- Ransomware usually deletes shadow copies (T1490 Inhibit System Recovery), but we did not observe Grief doing this. This could be because Grief was designed for the operator to manually delete shadow copies, or for some other reason. This is significant because if a victim has shadow copies enabled on a machine, they may be able to restore lost data. If you can confirm that you have observed shadow copy deletion in Grief incidents, please reach out to us.

- The Grief sample manipulated Windows Defender using Windows Registry modifications. We often observe malware issuing PowerShell commands to disable or modify Defender. In this case, Grief set the

Policies\Microsoft\Windows Defender\Real-Time Protection\LocalSettingOverrideDisableRealtimeMonitoringandPolicies\Microsoft\Windows Defender\DisableAntiSpywarekeys (T1562 Impair Defenses). These changes would intentionally counteract settings applied by administrators via Group Policy Objects. - Grief setting the system to boot from safe mode with minimal services available and no network connectivity is noteworthy because very few ransomware families do this.

- Grief has a peculiar way of setting itself up for persistence. It modifies a legitimate Windows Service configuration to run the malware. Grief selects a legitimate Windows Service and replaces the

ImagePathregistry value of the service’s configuration to execute the ransomware again at the next boot (T1543.003 Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service). This ensures that the next time the system starts, Grief runs again and returns the system to safe mode.

A note about indicators

Many teams include indicators of compromise in their blog posts. We have chosen to focus on behavioral detection opportunities instead, as we find these much more durable than sharing hash values that change quickly. Additionally, the hash value of the Grief sample we analyzed is specific to a single victim (as were many of the file names and IP addresses associated with the threat), meaning it will not be useful for future detection. The same is true for Dridex, as hashes change between victims. In the interest of helping researchers discover similar samples to ours, we do want to disclose the import table hash of the Grief sample:

E1433a76b58c119fa5508912c531e476

Huge thanks to Detection Engineer Dan Cotton for his contributions to this research.