When it comes to information security, it may seem like building an effective incident response (IR) program is about as complex as deriving E=mc², especially if you’re starting with a blank slate. Rest assured, this equation is a lot simpler and doesn’t require nearly as much time nor genius to solve (luckily, we have industry standards for that).

With information systems, people, processes, and policy all interwoven into the core of the IR function, producing a successful program requires participation at all levels of an organization as well as collaboration with external partners. What so many organizations fail to get right is that IR is a business problem, not a technology problem. Therefore, understanding which business parts make up an effective IR team is the first step in understanding this equation.

This blog will focus on company leadership, legal counsel, law enforcement, and regulatory agencies, but there are many more factors to consider when building your IR program. For a more comprehensive list, watch this mini masterclass on-demand.

Company leadership

An effective IR program is paramount to having a resilient security strategy, and the success of a 21st-century business relies, at least in part, on this initiative. According to our recent survey of 500 security leaders, 93 percent of organizations suffered a compromise of data within the past year, while nearly half of those had at least four such incidents. This underscores two points:

- The frequency of attacks proves that security incidents represent a present and persistent risk to your business.

- It is impossible for an organization to stop every threat that comes its way.

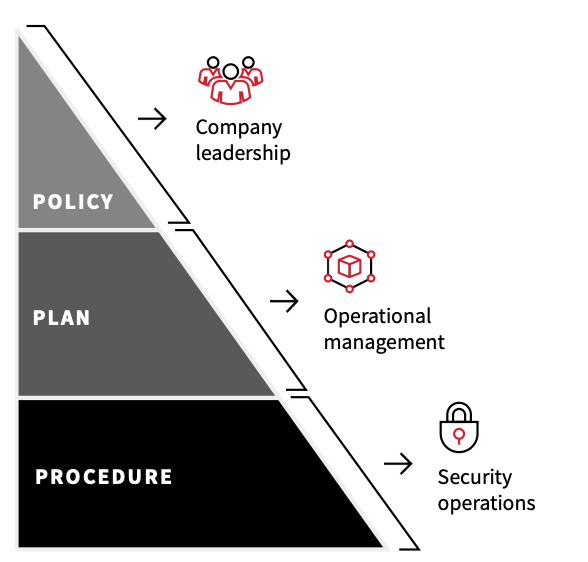

Ultimately, any organization that’s mature enough to observe and detect a threat in its environment will eventually face an incident, and it pays to be prepared and agile when that eventuality comes to be. Preparation starts with a well-defined policy that is prioritized by company leaders. Roles and responsibilities, performance measures, and reporting guidance are all components that require leadership oversight and input.

Tech people aren’t generally business people. We shouldn’t assume they grasp the priorities that drive a business toward success or failure, which is why the responsibility lies with the C-suite. Unanimously acknowledging the need and identifying the scope of the IR program is a leap toward maturity.

Legal counsel

Involving legal counsel when outlining the purpose and scope of an IR program is necessary because—let’s face it—words matter. When defining what an incident is, the choice in words could mean the difference between a lawsuit or accolades. Therefore, it is important to consult with your legal team to nail down the vernacular that will be shared both internally and externally.

Determining who to notify (and when) is another legal element often overlooked during the planning process. As security practitioners, it is easy to get bogged down by the process of handling an incident, and legal advisors can be thought of as external communication czars that ensure an organization is saying the right things, to the right people, at the right time. In good IR plans, they direct communication guidelines and mitigate risk and liability.

Beyond defining what constitutes an incident and helping develop the IR plan, you’ll want to work with your lawyers when sorting out the scope of work with a third-party incident response partner.

Security operations

Whether an organization has an in-house security operations center (SOC) or is outsourcing the job, knowing who is taking point on dealing with incidents is essential knowledge for the entire function. Enterprises with a seemingly endless budget may have mostly in-house capabilities, third-party services such as Managed Detection and Response (MDR), and external IR partners on retainer with varying degrees of authority and responsibility. Small to medium-sized companies may choose to go all in with an MDR or other managed security service provider (MSSP) due to value and lack of internal proficiency and tools.

Whatever the case, identifying and working with the team in the trenches during the planning stage will ultimately shape what actions are needed in the procedure phase of the IR buildout. Your SOC analysts and other security and IT staff must know what triggers the incident response plan and their role in the plan once it’s been triggered. Just as importantly, everyone needs to be on the same page about the definition of success for any incident response engagement.

Law enforcement

One of the reasons we don’t see more convictions when it comes to cybercrime is because many organizations don’t know how or when to properly report an incident. You absolutely don’t want to pick up the phone and call the FBI every time someone opens a phishing email, but there are numerous circumstances in which you 100 percent should reach out to a local or even a federal law enforcement agency. It’s important to understand the kinds of incidents that warrant notifying law enforcement. Thankfully, the Justice Department has a handy guide on how, when, and what to report.

As part of the planning process, organizations should designate an internal point of contact to acquaint themselves with proper reporting procedures and channels to expedite the partnership with law enforcement authorities.

The average cost of a data breach is $3.86M (and could run as high as $8.63M for organizations in the United States). With that in mind, it’s imperative organizations do their part in seeking justice, not only for their bottom line, but for the sake of their customers and the global community at-large.

Regulatory agencies

As more of our infrastructure goes digital, heavier regulations are being imposed within the cyber landscape. Various laws require notification to regulators if certain sensitive information is involved in the incident. Stricter reporting requirements have been set forth for federal agencies, though private sector best practices remain largely unregulated.

Organizations are encouraged to report security incidents to the Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA) via the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC). The agency provides a variety of risk management and response services if your organization is just starting on its journey of building out an IR function. More importantly, sharing intelligence from an incident can help other organizations defend themselves against similar threats—and it can open the door to additional support when dealing with sophisticated attacks. To learn more about when and how to report an incident to CISA, read its guidance on reporting an incident.

Adding it all up

Each of these components, both internal and external, add to the overall value of an IR program. Think of it this way: When an organization is taken offline due to a ransomware attack or is hacked by suspected state actors who’ve managed to compromise its servers (as was the case with SolarWinds), it’s not IT you’re going to run to, it’s your entire IR function. The whole is truly greater than the sum of its parts when it comes to protecting your organization.