Security operations is a term that describes the set of functions required to put specific objectives for your information security program into practice, or into operation.

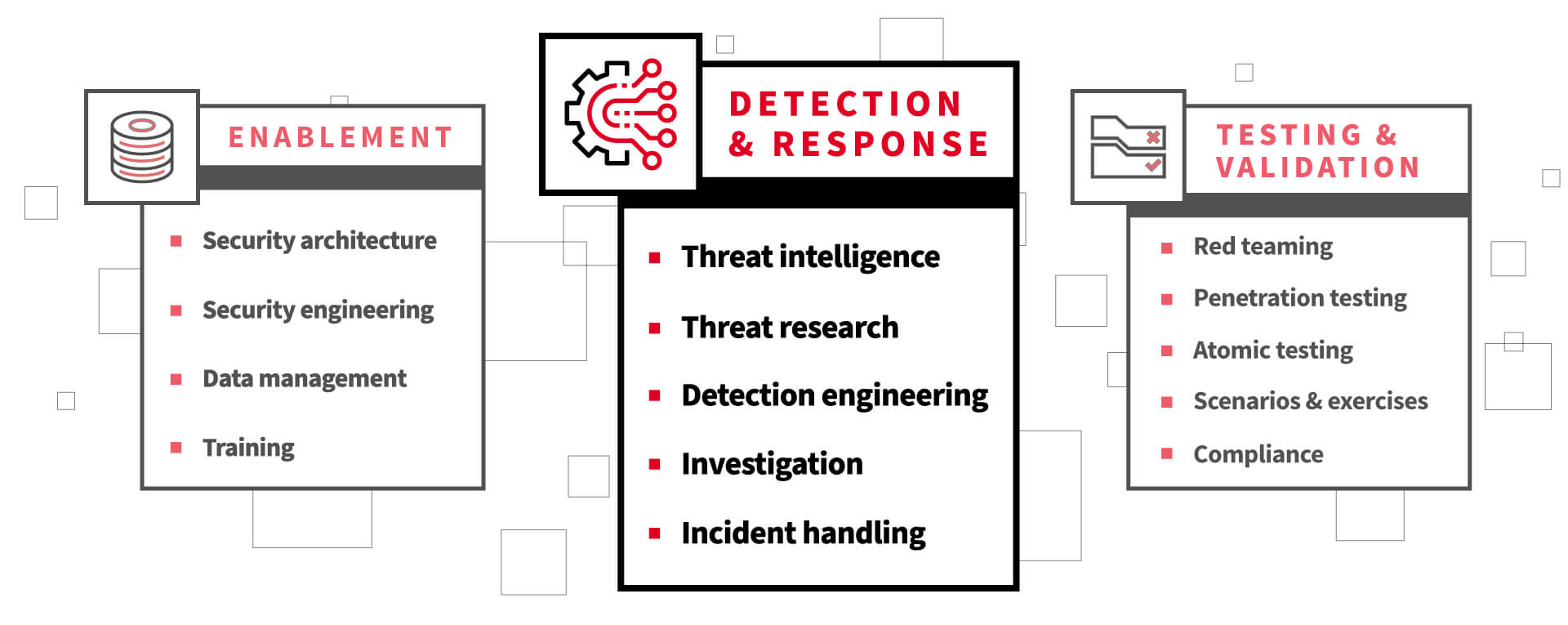

Definitions of security operations vary widely. To help get us all on the same page for this discussion, here are various components comprising a modern security operations center (SOC) organized into three functional areas, as is broken out below.

This three-part series will cover each of these areas in detail, starting with the core threat detection and response functions:

- Threat intelligence

- Threat research

- Detection engineering

- Investigation

- Incident handling

While these functions are distinct from one another, they must be tightly integrated. Often, these functions rely on one another to a certain extent, with one function informing the actions taken in the next function. To achieve tighter alignment, or in the interest of meeting budgetary constraints, organizations often opt to combine these functions or have them provided via partners.

Threat intelligence

We’ll start with threat intelligence, which is a cornerstone of high-functioning security operations. A threat intelligence function begins with the organization’s threat model, used to identify relevant threats. Once identified, the intelligence team attempts to understand and classify these threats so that they can help prioritize them.

Ultimately, threat intelligence is a decision-making resource. Using a threat model as its primary input, the intelligence team may produce a variety of outputs that can be used to inform decisions ranging from strategic to tactical:

- Investments in security technology or expertise, either in-house or provided by others

- Data sources, used to gain visibility into and ultimately detect threats

- Controls, both preventative and detective, used to prevent threats whenever possible, and otherwise enable investigation and incident response

- Prioritization of specific activities for other teams, like helping the detection engineering team prioritize their backlog of analytics

- Context for analysts or incident responders, helping them draw faster, better-informed investigative conclusions

Again, depending on the organization, the responsibility of this function can be dedicated to a person, performed by a team, or shared amongst other functions. Being explicit about the purpose of your intelligence function and having an ability to operationalize the intelligence that you produce or consume are the only barriers of entry.

Intelligence teams have a superpower. We don't just say "you should do this", we get to say "you should do this BECAUSE…." This makes a big difference. "You should look for adfind because ransomware operators have used it for discovery" is more powerful than "Look for adfind".

— Katie Nickels (@likethecoins) November 10, 2020

For those looking for a deeper understanding of threat intelligence here at Red Canary and beyond, or those considering entering the field, see these additional resources:

- Getting started in cyber threat intelligence: 4 pieces of advice

- Remapping Red Canary with ATT&CK® sub-techniques

- Red Canary’s 2020 Threat Detection Report

- A Bazar start: How one hospital thwarted a Ryuk ransomware outbreak

Threat research

If the purpose of the intelligence team is to inform decision-making, some of the core activities associated with threat research are to:

- Ensure that identified intelligence priorities are sufficiently contextualized

- Identify emerging threats that may be poorly understood or not known at all, so that they can be prioritized

- Ascertain coverage blind spots and assumptions and offer practical recommendations for improving detection coverage

- Provide a level of depth with respect to attack techniques, threats, malware, and other types of analysis that can’t be optimized for time in the same manner as detection engineering or incident handling

The skills required for this team may vary depending on the technology that you’re charged with understanding. Some common traits include exposure to detection engineering, operating system internals, malware analysis, and offensive security. But more so than anything else, threat research requires both time and a willingness to go deep on technology, adversary tradecraft, or software as needed.

But more so than anything else, threat research requires both time and a willingness to go deep on technology, adversary tradecraft, or software as needed.

Detection engineering

The detection engineering function can be thought of as the working end of threat intelligence. They take the intelligence team’s threat profiles and prioritization as input with which to build the software and/or analytics that the team will use to detect those threats.

The detection engineering team is often the last stop before potential threats are surfaced for investigation, so this is often where accountability lies for ensuring that potential threats are not only accurately identified, but also packaged up properly for investigation. This includes ensuring that analysts have critical context related to a potential threat:

- Where it came from

- What it did

- Where it went

- What it might be

- What it might do next

If this sounds like a lot, it is. Nowhere will your level of maturity in all functions ranging from security architecture to threat intelligence be more apparent than here.

A great detection engineering team works every day on objectives that are at odds with one another. First, don’t miss things. Build detection coverage that has both breadth and depth, looking for as many adversary techniques as you can, and looking for each in ways that are increasingly thorough and resistant to evasion. At the same time, don’t inundate the investigative team with low quality investigative leads, false positives, or a lead that lacks context.

In practice, detection engineering doesn’t require specialized tools, but it does require a sound process. You may find yourself implementing detection analytics in an off-the-shelf product such as a SIEM. Or, you may define, build, and operate software that is uniquely suited to address complex, highly contextual detections. Platform aside, understand what you’re optimizing for. Either:

- Breadth of coverage, or a narrow set of high impact threats

- Detection that is fast, or detection that is thorough and highly accurate

For a deeper dive into detection engineering, see these additional resources:

- ATT&CK is only as good as its implementation: Avoiding 5 common pitfalls

- Detecting all the things with limited data

- Detection engineering: Setting objectives and scaling for growth

Investigation

Think of the investigative team as being analogous to an emergency room. Your first job is triage: Of the hundred things you might do right now, which is most important? In this area of security operations, the quality of your defensive telemetry, the maturity of your detection engineering function, and the thoughtfulness of your threat intelligence team will be on full display and readily apparent. Prioritizing threats according to their importance requires that the input to your triage process includes:

- Context related to the analytic(s) that resulted in the investigative lead, so that you understand why you’re looking at a given event in the first place

- An indication of the threat you might be investigating, as well as its expected impact

- Situational awareness, in the event that you’re staring down an event that is related to a very recent or active incident

Once you’ve implemented a good process and rhythm for triage, you now face competing pressures similar to those of the detection engineering team. You must:

- Investigate in a timely fashion to identify and shut down early stage intrusions

- But don’t be hasty or sloppy

- Be thorough in what you produce when you identify a confirmed threat

The primary objective of this function is to produce timely, complete, confirmed threat reports for action by the incident handling team. There are other objectives, but the overarching objective of any information security program is to reduce risk, and for an operational team, reducing realized risk in particular. With this in mind, analysts working closely with detection engineering to balance shared, competing objectives is critical to the success of the mission.

Incident handling

The incident handling team is critical to ensuring that identified threats are validated, understood with respect to scope and severity, contained, and eradicated. In the context of this model, the focus is on the activities that take place once a threat has been triaged, investigated, and confirmed.

Note that incident handling differs from incident response, which is generally defined as a much broader capability that starts with things like authority and policy, depends on the security operations team for identification of and response to incidents, and includes processes such as postmortems and feedback loops into the technology team. One way to think of incident handling is as the coordinator of operational functions within a broader incident response program.

Much has been written about incident response over the years, and organizations like NIST have done a great job of defining the key activities, processes, and measures of response effectiveness. Start with NIST Special Publication 800-61, the Computer Security Incident Handling Guide and go from there!

What’s missing?

Like any well-tuned operational capability, a great security operations team doesn’t stand alone. The technology upon which the operations team will work must be in alignment with their needs and objectives. And ongoing training, drilling, and testing of the end-to-end system are critically important so that the entire organization can operate decisively and with confidence in an emergency.

The next two articles in this series will cover enablement functions as well as the various testing and validation functions of security operations, showing how everything connects and outlining all the essential components of a modern SOC.

Read the second post in the series here, about enablement functions for the modern security operations center.